by Jack Vaughn, CAC Grader

Gold coins that have acquired toning are seen far less frequently than their silver counterparts. Why is this so? Gold is known for being a terrifically nonreactive or “inert” element. However, a small handful of gold coins recovered from the shipwreck of the S.S. Central America became toned at the bottom of the ocean. How did this happen?

Some Chemistry for You

Generally speaking, there are two types of corrosion: one that increases the metal’s surface area as the reaction progresses and the other that does not. When the metal’s surface area increases, more metal corrodes incrementally. Rust is an excellent example of this phenomenon. If a piece of iron is left outside to rust, the reaction will eventually eat through the metal. Conversely, tarnish is a thin layer of oxidation where the surface area does not increase as it forms. Tarnish remains attached to the metal’s surface while rust becomes discharged. Tarnish is responsible for giving a toned coin its color. Additionally, this layer acts as a barrier that protects the underlying metal. In chemistry, this is known as a “passivation layer” and is common on metals like silver, nickel, and copper.

Over long periods of time and under the right circumstances, gold will react with elements from the halogen family (fluorine, chlorine, bromine, and iodine.) Reactions between gold and the halogen gases do not yield a tarnish-like substance. Instead, the gold becomes discharged from the surface. If enough gold becomes discharged, eventually, nothing will be left. It is somewhat common to see miscellaneous shipwreck-recovered gold with a light porous effect.

Commercially, Aqua Regia is a powerful acidic solution used to dissolve gold. This solution contains roughly one part nitric acid and three parts hydrochloric acid. Aqua Regia’s key to dissolving gold is the presence of chlorine (a member of the halogen family) found within hydrochloric acid. Although chlorine is not acidic (or alkaline), the potent mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acids has a very low pH, accelerating the reaction between gold and the chlorine found within the hydrochloric acid. This reaction discharges gold from the underlying surface until no solids are left.

Practically, nitric acid was used during production of the 1907 St. Gaudens Ultra High Relief. The surfaces of these coins look strange because the metal on the surface is technically pure gold. Each of these pieces was struck nine times. Between each subsequent strike, the coins were submerged in nitric acid. This treatment dissolved the silver and copper impurities on the coin’s surface, leaving just gold. Nitric acid was used because it lacked any presence of halogens.

What Are Interference Colors?

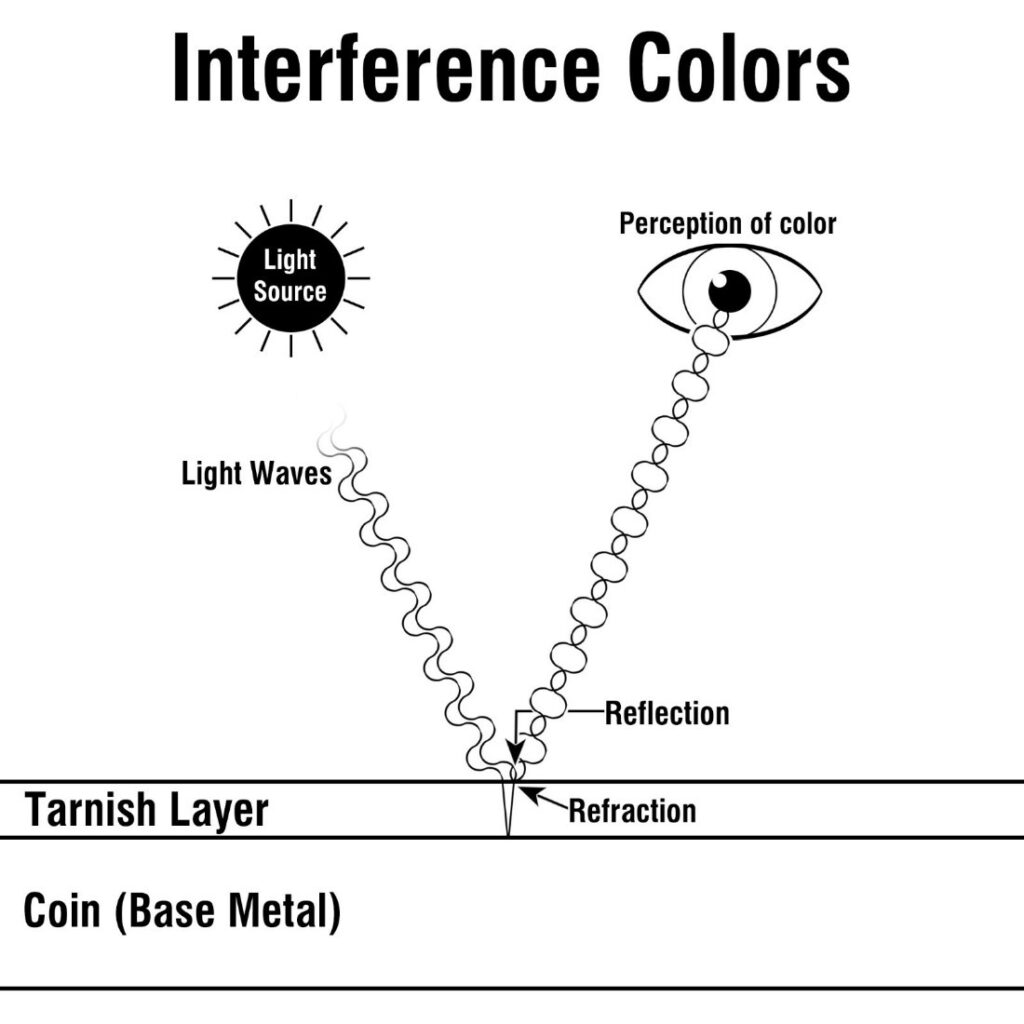

People often draw attention to oil-filled parking lot puddles that look like rainbows. This rainbow is a result of interference colors. The surfaces of a toned coin become tarnished. The puddle and a toned coin both have a thin, translucent layer coating the surface. Tarnished silver, copper, and nickel may exhibit many brilliant iridescent colors before eventually turning thick, opaque, or “terminal.” Interference colors are a by-product of “translucent tarnish.”

Translucent tarnish and the underlying metal reflect, absorb, and refract light differently. Refraction is when the direction of light is bent as it passes through a medium of different density. For instance, a straw appears to go off in a different direction when placed into a glass of water. When light hits a toned coin, some rays reflect directly off the tarnished surface, while others refract through it. During refraction, the tarnish will absorb some light. This absorption has an effect on the light that reaches the viewer’s eye. When refracted and reflected light rays hit our retina, the different wavelengths interfere. This interference of light makes us perceive a color.

As the layer of tarnish grows thicker, it absorbs more light, resulting in different interference colors or “toning.” Tarnish that has become thick enough to be opaque is known as opaque or “terminal.” The light that travels into a terminal layer of tarnish is absorbed entirely, eliminating the opportunity for interference colors to occur. Terminal silver appears black, while copper appears green.

Show off Your Collection in the CAC Registry!

Have CAC coins of your own? If so, check out the CAC Registry–the free online platform to track your coin inventory, showcase your coins by building public sets, and compete with like-minded collectors!

Toning on Central America Gold

It is not uncommon for shipwreck-recovered gold coins to have a porous “saltwater effect.” This effect results from chlorine, an abundant element in seawater (19,000 ppm.) Like Aqua Regia, the chlorine will have a larger effect on the gold as the acidity of the surrounding water increases. Remarkably, the gold aboard the S.S. Central America was surrounded by limestone – an alkali mineral that helped to neutralize the surrounding water’s acidity. This pH change minimized the chlorine’s effect on the gold and left the coins unharmed. Like Aqua Regia, the chlorine-saturated water would have had a more significant effect on the gold if the water’s pH were higher in acidity.

1857-S $20 PCGS MS67, CAC approved.

ex Legend Auction 05/2019.

Images courtesy of Legend Auctions.

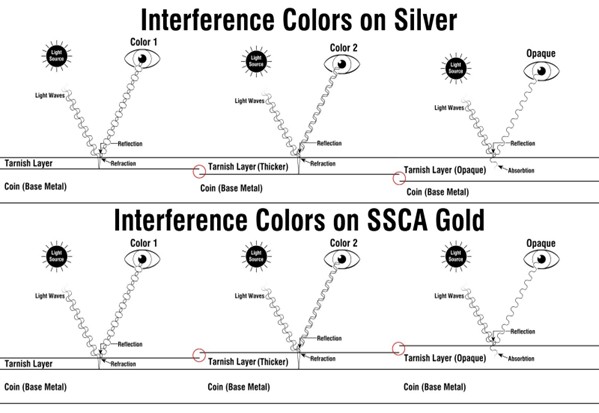

So how did the gold tone? Technically, it did not. Once the S.S. Central America sank, iron beams, once integral to the ship’s structure, became heavily corroded. Over time, countless particles of iron oxide (rust) were discharged from the surface of these beams and dissolved into the water. These tiny particles precipitated onto the gold coins beneath and adhered to their surface. This event created a tarnish layer similar to what we see on silver coinage. In addition to the limestone neutralizing the water’s pH, this layer acted as an artificial passivation layer and helped further shield the underlying gold from the surrounding water. The few pieces that display an array of colors have a deposit of iron oxide thin enough to be translucent and bring about interference colors.

In the diagram above, the layer of silver tarnish seeps further into the metal’s surface before eventually becoming opaque. The tarnish layer on silver differs from that found on gold recovered from the S.S. Central America—it becomes thicker through the addition of iron oxide precipitate. Toned gold coins aboard the S.S. Central America are the unlikely result of many chaotic factors aligning. For shipwreck gold to tone, it must be under uncommon circumstances.