by Greg Reynolds

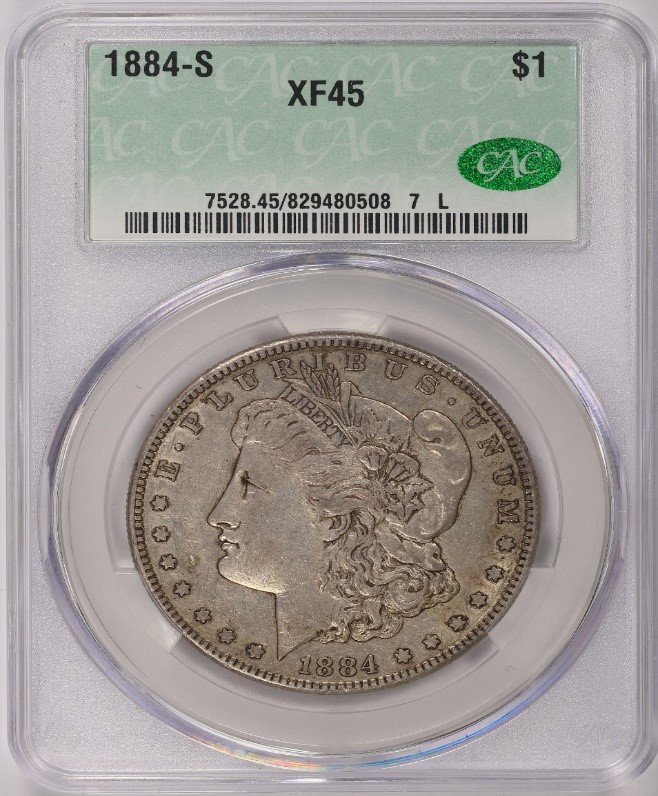

The first phase of Morgan silver dollars (1878-89) was detailed in a separate discussion, which is available on the CAC site. The second phase (1890-1904), a continuing production of Morgan dollars in massive quantities, was the product of an ill-fated political movement to further the goals of silver advocates, including addressing deflation.

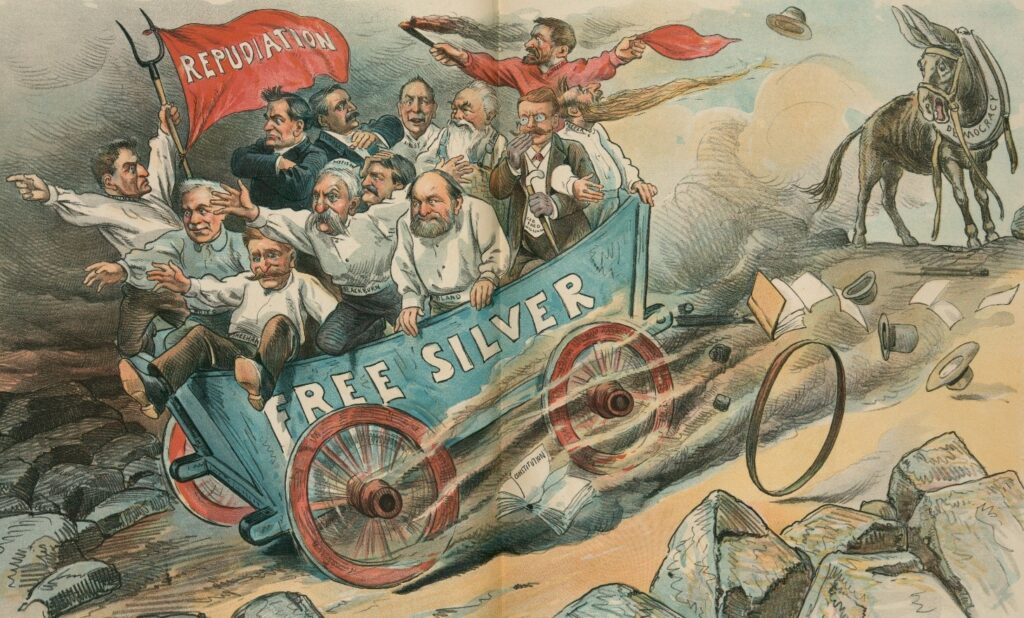

The second phase heavily contributed to an economic downturn and the worst financial crisis in the history of the U.S. Federal (National) Government. Morgan dollar production became central to a deep political conflict and Morgan dollars themselves were symbolic of bitter and destabilizing political divisions in the U.S. Massive silver purchases by the government and consequential Morgan dollar production substantially changed the history of the United States.

In review, the driving forces behind the origins of Morgan dollars (and the first phase of production) pushed for increases in the market price of silver as a metal (bullion) and demanded that the legal tender status of silver coins be restored such that citizens would have the legal right to pay debts in silver coins, in accordance with historical standards since the Mint Act of 1792! They favored bimetallism, not just to continue a tradition, really as a way to benefit owners of silver, industries related to silver, farmers, poor people who had little use for gold, and people in debt.

Metal Ratios and Weights for Silver Dollars

Bimetallism involves the standard unit of currency in a society being linked to precise weights of gold and silver. A policy of bimetallism requires that the values of gold and silver be tied to each other through an official government ratio, which is maintained by the government through monetary policy.

Silver advocates focused on the 16 to 1 silver to gold ratio that was established in 1834; one ounce of gold was required to be worth sixteen ounces of silver. As an example, ten 1838 half dollars (in total), weighed about sixteen times as much as one 1838 $5 gold coin. Actually, the legal ratio established in 1834 was a micro-fraction less than 16:1, but 16:1 was the closest approximation that people remembered.

That legal ratio and its inconsistency with changing market realities were at the center of a bitter debate, which rocked the nation. Silver related policies and the gold standard were leading issues in the presidential campaigns of 1888, 1892, 1896 and 1900! At times, the monetary role of silver was the paramount national issue in political campaigns.

Except for silver dollars until 1873, U.S. silver coins minted from 1853 to 1877 were not legal tender for substantial payments. Their status as ‘true money’ had been eliminated.

With the passage of the Bland-Allison Act in 1878, silver advocates and connected political forces brought about the production of hundreds of millions of Morgan dollars, which were legal tender. In theory, Morgan dollars could be used to pay any debt in the United States, though they were rarely used for substantial transactions.

Pro-silver political forces aimed for the Bland-Allison Act to pave a path for the reinstatement of a policy of bimetallism, the reviving of the 16 to 1 silver to gold ratio from the Coinage Act of 1834, and the traditional valuation of silver such that one U.S. dollar equaled 371.25 grains (0.7734 Troy ounce) of silver. These were not imaginary or farfetched demands. The pro-silver agenda stemmed from policies that really were in effect in the past and was partly based upon impractical laws that were still ‘on the books’! Indeed, during the late nineteenth century, proposed silver-based policies sounded sensible and appealing to a large portion of the U.S. population.

Much of the background is covered in my discussion of the origins and first phase (1878-89) of Morgan dollars. I theorize that, during the first phase (1878-89), there were semi-realistic hopes and serious plans for silver dollars to be used very often for consumer purchases and the payment of debts. During the second phase (1890-1904) of Morgans, silver dollars were more conceptual, political and symbolic. Their advocates knew that they would not be widely circulating. I further theorize that Morgan dollars minted during the second phase were not then intended to circulate. Silver advocates sought for Morgans to be stored indefinitely in government vaults in order to raise the price of silver by reducing the available supply. Importantly, even though silver advocates knew that they could not achieve their primary objectives during the 1890s, they intended to influence the monetary order.

The Bland-Allison Act of 1878 authorized new silver dollars, which were to be Morgans, and re-established the old standard, which originated in the Mint Act of 1792, 371.25 grains of silver in each silver dollar, which equals 0.7734 Troy ounce. A then obsolete and impractical definition of a U.S. dollar was legislated again.

By chance, 371.25 grains (0.7734 Troy ounce) of silver, the amount in a silver dollar, had a market value of around one dollar during 1873. This fluke occurrence provided evidence for silver advocates to persuade many people that the traditional standard silver dollars, the 16 to 1 silver to gold ratio, and the old policy of bimetallism were all viable in the 1870s. By 1890, however, it was clear that such policies were no longer practical.

The Market Value of Silver

According to David K. Watson, in his History of American Coinage (New York & London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1899, p. 122), the market value of the silver in a silver dollar was around $0.891 in 1878, $0.859 in 1883, and $0.723 in 1888. It bounced to $0.809 in 1890, probably because silver advocates then speculated that further government efforts to drive silver upward would be successful. By 1892, however, the silver in a silver dollar was worth $0.673 and just $0.491 in 1894. By 1898, the value was around $0.45, just forty-five cents of silver in a silver dollar!

Watson reported averages for respective years. There were surges upward or sharp drops downward during twelve-month periods. It makes sense to think about the value of silver over a period of years, not ‘day by day’ fluctuations. The downward trend in the value of silver bullion during the 1880s and 1890s provided political fuel for silver advocates yet made their policy proposals seem even more impractical than they already appeared.

According to eminent economist J. Laurence Laughlin, from 1845 to 1849, the monthly average silver to gold, free market ratio varied between ‘15.62: 1’ and ‘16.05: 1.’ In regard to silver to gold ratios, annual averages during the 1840s demonstrate that bimetallism was then practical: 1845 15.93; 1846 15.91; 1847 15.82; 1848 15.87; and 1849 15.81. To be clear, “15.81” means a silver to gold ratio of 15.81 to 1; one ounce of gold was worth around 15.81 ounces of silver at that time. U.S. silver and gold coins widely circulated alongside each other during that period.

From 1845 to 1849, the real market levels were close to the government established 16 to 1 ratio in the Coinage Act of 1834. Increases in the supply of gold, mostly from discoveries in California, caused the relative value of silver to increase. As the supply of gold increased the value of gold decreased, and each ounce of silver was then worth more gold, as the California Gold Rush impacted the economy.

From 1851 to 1856, one ounce of gold was often exchanged for less than 15.5 ounces of silver; an ounce of gold was no longer worth close to sixteen ounces of silver. The market value of gold fell way below the 16:1 legal standard.

After 1855, the free market, silver to gold ratio fluctuated like it never had before. It became questionable as to whether it was even possible for the U.S. government to maintain a fixed silver to gold ratio, thus many U.S. citizens concluded that bimetallism had become very impractical. A majority of Americans, especially people living on the East Coast, favored a gold standard rather than a joint silver and gold standard (bimetallism).

Silver and Morgan Dollars in Politics

The political trend in favor of a gold standard galvanized advocates for silver, who prepared themselves for a long and intense political battle. They maintained that they were not only fighting for a metal; silver advocates declared that they were fighting for farmers, Southerners and poor people.

Silver became indicative of a very controversial political agenda. The production of Morgan dollars to some extent caused and was reflective of a bitter and polarizing political conflict.

From 1794 to 1873, the U.S. government minted a total of less than eight million silver dollars. After 1878, it was common for more than ten million silver dollars to be struck during one year. In 1890 alone, more than thirty-eight million were produced. By 1904, the total mintage of Morgan silver dollars surpassed a half-billion!

The second phase of Morgan dollars (1890 on) was powered by farmers plus others connected to agriculture and by people who kept savings in silver, including coins, bars, candlestick holders, utensils, plates, etc. While most people had just small amounts of silver, the grand total of all the silver owned by relatively less affluent people was significant and of importance to them! Moreover, silver in general and the Morgan dollar in particular became symbolic of differences in income and lifestyle. Relatively affluent people and skilled laborers on the East Coast benefited greatly from economic growth during the second half of the nineteenth century.

There were many people in the Midwest and South who were not prospering, though the reasons why were complicated. Possible benefits of silver-related policies were exaggerated.

Were silver advocates telling the truth about business activity under the gold standard? Was a substantial portion of the U.S. population really hurting between 1870 and 1900? Was it honest to suggest that government purchases of silver bullion and the revival of the standard silver dollar would enhance the well-being of millions of U.S. citizens?

“The rapid expansion of industrialization led to real wage growth of 60% between 1860 and 1890,” it is noted in the Wikipedia, and this conclusion stemmed from government data compiled during the nineteenth century. Largely due to deflation, nominal wage growth was not nearly as high.

While prices are falling, the same wage in nominal terms becomes greater in real terms, as each dollar can then buy more goods and services. There is no easy or completely scientific way to figure changes in real wages and real Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the value of the economic output within a nation, though many economists agree upon some standard methods.

Show off Your Collection in the CAC Registry!

Have CAC coins of your own? If so, check out the CAC Registry–the free online platform to track your coin inventory, showcase your coins by building public sets, and compete with like-minded collectors!

Economic Growth and Downturns

In nominal dollars, U.S. GDP increased from $7.81 billion in 1870 to $20.76 billion in 1900. In “2012 dollars,” according to measuringworth.com, historical sums converted to reflect the value of the U.S. dollar in the year 2012, real GDP increased from $127 billion in 1870 to $480 billion in 1900, almost four times as much!

The U.S. population increased,too. Even so, real GDP per person almost doubled from 1870 to 1900. Though there were occasional economic downturns, true growth of more than 5% during any one year was not unusual. From 1897 to 1898, GDP increased by nearly 11% (measuringworth.com), after adjustments for deflation or inflation.

Although there is no perfect way to accurately and fairly report historical data, Christina Romer is widely recognized as an expert in historical GDP and GNP compilations. She is a former president of the American Economic Association (2022) and a former chairman of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers (2009-2010).

In 1986, Romer criticized and revised earlier, accepted GNP (slightly different from GDP) data. Adjusted for ‘1929 dollars,’ a fair common denominator as 1929 was just before the turmoil of the Great Depression, Romer figured that GNP in 1870 was $10.593 billion and GNP in 1900 was $37.621 billion, indicating a growth rate of 4.17% per year.

It is interesting to reflect upon the growth rate before the 1893-94 recession, a painful downturn which was partly caused by the Morgan dollar production and storage program. In ‘1929 dollars,’ Christina Romer stated that GNP in 1892 was $28.995 billion, indicating an annual growth rate of 4.48% from 1870 to 1892.

Accepted data demonstrates that incomes rose markedly from 1870 to 1900, though not for everybody during every year. During the late nineteenth century, silver advocates often argued that ‘the poor were getting poorer’ and that wage-laborers were suffering while the gold standard was in effect. Does expert analysis of nineteenth century data support such a conclusion?

Stanley Lebergott has analyzed nineteenth century economic data. During the middle of the twentieth century, Lebergott was about as famous as a career government statistician and economist could be, and he was a professor at Wesleyan University for decades. Some of the data that he compiled was challenged by respected economists in later times. Even so, Lebergott’s work is considered accurate enough for general conclusions.

Lebergott was certainly not a supporter of the gold standard or of the economic policies in effect during the late nineteenth century. Moreover, he was very concerned about the plight of relatively poor people, and the incomes of women. Nonetheless, Lebergott’s research and statements regarding wages boldly show that he found that ‘real wages’ greatly increased in the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century.

During the 1890s, the pro-silver agenda and the agricultural sector were closely intertwined, partly because many farmers were harmed by deflation and struggled with business debts. Indeed, silver advocates argued that the gold standard and related policies resulted in extreme hardships for farmers and employees of farmers. Lebergott’s data indicates, however, that from 1850 to 1899, wages for farm laborers increased by 35%. In manufacturing industries that focused on cotton and wool, wages increased by 56% and 71%, respectively.

Again, according to Lebergott, nonfarm wages rose by 57% from 1850 to 1899, yes fifty-seven percent! Certainly, all economic data, especially from past centuries, can be significantly off-target, especially in cases where adjustments must be made for deflation or inflation. Nevertheless, Lebergott’s work is exceptional and thorough, with clearly credible sources.

Researchers may refer to Stanley Lebergott’s Labor Force and Employment, 1800-1960, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research in 1966, as part of a project compiled by Dorothy S. Brady. Although researchers can always find imperfections in data, silver advocates did not provide much evidence to support their agenda.

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act Brought Economic Disaster

Indisputably, the demonetization of silver did not have the harmful effect on the economy that silver advocates claimed that it had. Any plausible interpretation of surviving data suggests that there was then strong economic growth and substantial growth in wages, after adjusting for deflation.

The poor were not becoming poorer, and laborers were not treated any more unfairly while a gold standard was in effect than they were at any other time before 1900. Moreover, by the late 1870s, it became extremely apparent that it was not a good idea for people to keep their savings in silver. The central argument by the silver advocates that government propping of silver, with taxpayer supplied gold, would somehow be very beneficial to debtors, poor people, farmers, people with modest savings, and Southerners, was not substantiated.

In 1890, many farmers, debtors, Southerners, laborers, and poor people honestly favored two new laws, the McKinley Tariff Act and the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. Unfortunately, these two new laws were the leading contributors to an economic disaster.

During the late nineteenth century, both Democrats and Republicans believed that aggressive tariffs (taxes on imports) would lead to higher wages and more robust business activity in the United States. Since the middle of the twentieth century, however, most economists in the U.S. and the U.K. have tended to oppose tariffs on goods imported from friendly nations. Indisputably, tariffs lead to higher prices for consumers.

Silver advocates, farmers and many people in debt favored higher prices to offset the deflation that had been occurring, yet higher prices harmed people, too. Someone who has to spend more money for food or clothes has less money to spend on other things. One reason why Morgan dollars were mass produced was the belief that government spending on the silver to mint Morgans would increase the money supply and stimulate the economy.

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 required the government to buy 4.5 million Troy ounces of silver per month to mint still more Morgan silver dollars, even though most of the hundreds of millions already minted never circulated and remained in government vaults. Moreover, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act mandated that the government pay for silver bullion with new issues of U.S. Treasury notes (paper bills), which were themselves redeemable in either gold coins or silver dollars at the “discretion” of the Secretary of the Treasury.

In theory, this was a way of even more greatly increasing the demand for silver and increasing the money supply. Essentially, the government was ‘printing’ new money to buy silver bullion. If these U.S. Treasury Notes (a form of paper money) had been redeemed in silver (traded back for silver), then the U.S. Treasury’s gold reserves would not have been jeopardized. The Sherman Silver Purchase Act, however, was written in such a way that the Secretary of the Treasury would feel obligated or be pressured to use gold coins (or gold-backed deposits) to redeem the paper money that was printed to buy silver bullion.

Indirectly, the government was purchasing silver bullion with taxpayer supplied gold, as the newly issued paper money was redeemed in gold. The Morgan dollar continuation incorporated into the Sherman Silver Purchase Act was a major factor in causing a brutal recession because the paper money used to buy silver to produce Morgans was later returned in exchange for gold (or gold-backed deposits) and the U.S. Treasury’s gold holdings were depleted. The government needed gold to pay its bills, and a large loss of the government’s gold led to a financial crisis.

Could the Secretary of the Treasury have prevented or lessened the severity of the ‘Panic of 1893’ by redeeming U.S. Treasury Notes in Morgan dollars rather than in gold coins? The Sherman Silver Purchase Act emphasized the “established policy of the U.S. to maintain” silver and gold “upon a parity with each other” in accordance with the 16 to 1 “legal ratio”!

This law essentially featured a provision that the government must buy silver to steer relative prices in the direction of the long obsolete, 16 to 1, silver to gold ratio, which had become dramatically inconsistent with market realities. The free market, silver to gold ratio was, by then, well above 20 to 1, most of the time.

The Secretary of the Treasury must have concluded that he was legally required to redeem the U.S. Treasury notes (newly authorized paper money) in gold in order to comply with the objectives of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. It may have been the only manner for the Treasury Secretary to even attempt to lower the silver to gold ratio and increase the value of silver. The law required the implementation of a policy that was impossible to implement, as there was then no viable strategy to bring about a 16:1 ‘silver to gold’ ratio.

The U.S. Treasury needed gold for particular obligations, including some bonds and payments to European banks. In his epic treatise, The U.S. Mint and Coinage (NY: Arco, 1966), Don Taxay declared that “the exportation and hoarding of gold had reached new peaks, and the nation found itself hurtling towards insolvency” (p. 274). Many banks failed and a large number of factories closed. The level of unemployment increased markedly. In 1893, President Grover Cleveland came to the conclusion that the economy had been severely damaged by mass purchases of silver and the consequent production of Morgan silver dollars.

“The President of the United States moved thereto by the business depression and financial disturbances everywhere prevailing, and assuming that the present condition of the country is the result of the operation of the so-called Sherman law, has convened Congress in extraordinary session and urged upon it his message of today the immediate repeal of the” Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890, Senator J. N. Dolph of Oregon declared on August 8, 1893. Viewpoints by leading commentators on the silver controversy, including remarks by Senator Dolph, were published in 1895 in a volume edited by Trumbull White, Silver, and Gold or Both Sides of The Shield. This book was famous in its own time and was later viewed by historians as fairly reflective of the deep political divisions that characterized the 1890s.

The Ceased Production of Morgan Dollars, Until…

By early 1895, the U.S. Treasury’s gold reserves had fallen to dangerously low levels. The U.S. government became desperate and borrowed a large quantity of gold from a semi-secret syndicate of banks. J. P. Morgan, the Drexel firm, and the Rothschild family were all involved. The financier J. P. Morgan was not related to George Morgan, the designer of the Morgan silver dollar.

The Morgan dollar production and subsequent storage brought about by the Bland-Allison Act of 1878 and the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 nearly bankrupted the government of the wealthiest nation in the world! The U.S. Treasury, though, continued to keep millions of Troy ounces of silver bullion and hundreds of millions of Morgan dollars in vaults.

Section 34 of the War Revenue Act of June 13, 1898 stated that “the Secretary of the Treasury is hereby authorized and directed to coin into standard silver dollars as rapidly as the public interests may require, to an amount, however, of not less than one and one half millions of dollars in each month, all the silver bullion now in the Treasury purchased in accordance with” the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of July 14, 1890 (David Watson, History of American Coinage, 1899, pp. 178-179).

By 1904, the silver bullion that had been purchased under the Sherman Act was gone. As it required more silver to mint one Morgan dollar than to mint two half dollars or four quarters, there was no longer a reason to mint Morgans, which never really served much of a purpose in commerce.

Since 1873, two half dollars had been specified to contain 347.22 grains (=2*0.9*192.9045) of silver. Four quarters or ten dimes also contained a total of 347.22 grains (= 22.5 grams = 0.723375 Troy ounce). Since the 1790s, one silver dollar has been specified to contain 371.25 grains (0.7734 Troy ounce) of silver. It was never cost-effective or sensible to produce Morgan dollars; the U.S. Mint was forced to do so by law.

I hypothesize that, by the 1880s, advocates of Morgan dollars were not really intending for them to be used as coins. The political forces behind the laws that authorized the production of Morgan dollars preferred that they remain hidden in government vaults. Morgan dollar production and storage were a mechanism to remove silver from the economy at the expense of taxpayers and were central to an agenda to restore bimetallism at a below-market silver to gold ratio. Silver advocates incorrectly maintained that large-scale government silver purchase programs and the minting of millions of Morgan dollars would lead to a more efficient and just economy; it led to a disaster that damaged the nation and could have been much worse. The resumption of Morgan dollar production in 1921 was a different matter and is covered in my discussion of the third phase.

Images are copyrighted by DLRC (www.davidlawrence.com).

Copyright © 2023 Greg Reynolds

About the Author

Greg is a professional numismatist and researcher, having written more than 775 articles published in ten different publications relating to coins, patterns, and medals. He has won awards for analyses, interpretation of rarity, historical research, and critiques. In 2002 and again in 2023, Reynolds was the sole winner of the Numismatic Literary Guild (NLG) award for “Best All-Around Portfolio”.

Greg has carefully examined thousands of truly rare and conditionally rare classic U.S. coins, including a majority of the most famous rarities. He is also an expert in British coins. He is available for private consultations.

Email: Insightful10@gmail.com