by Greg Reynolds

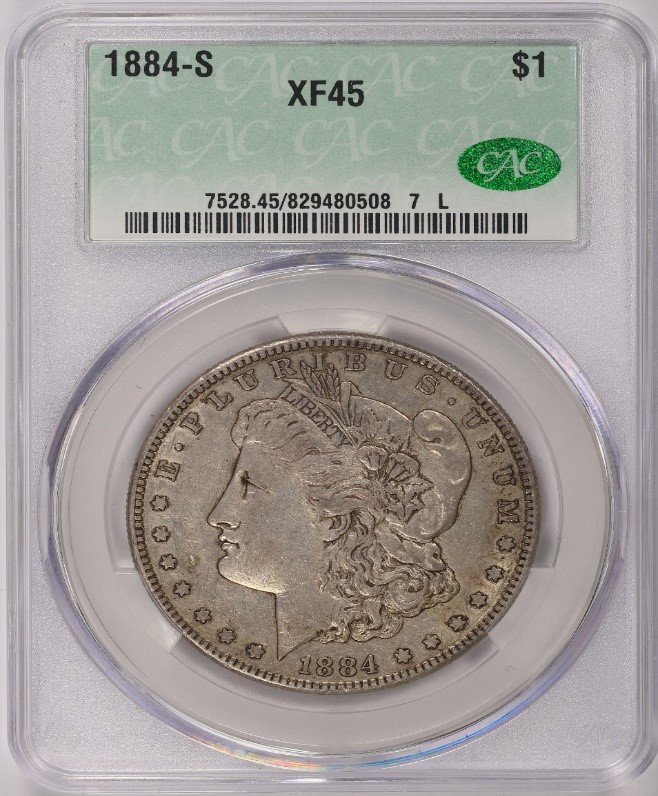

Morgan silver dollars are owned by hundreds of thousands of collectors. An incredibly large number survive, literally millions. These are the least scarce of all types of nineteenth century U.S. coins. They are named after their designer, George Morgan, then an employee of the U.S. Mint. Morgan dollars were produced from 1878 to 1904 and again in 1921. In honor of the one-hundredth anniversary of the end of the Morgan dollar, the U.S. Treasury Department issued fantasy Morgan dollars in 2021.

As silver dollars circulated to a minimal extent in the nineteenth century and hardly at all from 1851 to 1877, why were Morgan dollars authorized? Why were hundreds of millions produced?

The Minting of Morgan Dollars

The reasons why Morgan Dollars came into existence, and were minted for more than twenty-five years, stem from the market for silver as a metal (bullion), the political role of silver in the history of the U.S. monetary system, the use of silver coins rather than gold coins by less affluent people, and especially silver-related business interests in the United States. The gigantic mintages of Morgan dollars, totaling in the hundreds of millions, were incredibly distinct from the relatively low production and very limited role of silver dollars before 1878.

U.S. silver dollars were first minted in 1794. During the 1790s, there were relatively high mintages of them in comparison to mintages of other denominations of U.S. coins. Before 1816, however, more than three-fourths of the silver coins circulating in the United States were from the Spanish Empire.

During the nineteenth century, the use of U.S. silver dollars as money was extremely limited. After a mintage of more than 200,000 in 1800, silver dollars were struck in modest amounts from 1801 to 1803. If any were minted in 1804, those were probably dated ‘1803.’

U.S. silver dollars were not struck again until ten or so backdated Proof “1804” silver dollars were minted in 1834 and/or 1835, eight of which survive. In comparison, large quantities of half dollars were produced from 1806 to 1833, while zero U.S. silver dollars were minted. As examples, almost 1.4 million halves were struck in 1808, more than 1.4 million in 1809, 1.6 million in 1812, 2.2 million in 1819, 4 million in 1826, nearly 5.5 million in 1827, 5.9 million in 1831 and 5.2 million in 1833.

A total of less than two thousand silver dollars were struck from 1836 to 1839; these were Gobrecht dollars, a new design type. which were long thought to be patterns rather than coins. In the middle of the twentieth century, eminent researcher R.W. Julian demonstrated that Gobrecht silver dollars struck in the 1830s had the legal status of coins. They were formally delivered by the department of the coiner to the Philadelphia Mint superintendent and then released as money to banks. Even so, Gobrecht silver dollars (1836-39) were extremely scarce in their own time; few Americans even saw one. Liberty Seated silver dollars were introduced in 1840 and produced to a modest extent.

The total production of silver dollars during the 1840s was just a fraction of the total number of half dollars minted in the same decade. For example, the largest mintage of silver dollars during the 1840s was about 185,000 in 1842. For most of the decade, annual mintages of silver dollars were less than 100,000 per year. Even then, a sum of $100,000 was not a lot of money in the context of the economy of the United States. Mintages of Liberty Seated silver dollars (1840-73) were insignificant as parts of the nation’s money supply.

In 1843 alone, 3,844,000 half dollars were minted in Philadelphia and 2,268,000 were produced at the New Orleans Mint, for a total of more than six million half dollars. In contrast, around 165,000 silver dollars were produced during 1843. There is a large difference between six million half dollars and 165,000 silver dollars!

In 1846, less than 170,000 silver dollars were minted, yet more than 5.5 million half dollars were produced, more than thirty times the number of silver dollars. Furthermore, more than 3.5 million half dollars and less than 63,000 silver dollars were released in 1849. Among businesses and the general public, there was minimal interest in silver dollars during the 1840s, and silver dollars played even less of a role in commerce afterward.

Tracing U.S. Silver Coins

By the early 1850s, U.S. silver coins of all denominations ceased circulating, except for Three Cent Silvers introduced in 1851. Towards the end of the 1840s, large quantities of gold were discovered in California. As the supply of gold available increased to a great extent, the value of gold fell. A greater supply of gold caused silver to be worth more, though the rise in the value of silver during the early 1850s was not overwhelming. It was really the downward trend in the value of gold and the instability in the values of both metals that rattled the whole U.S. monetary framework, rather than the extent of the increase in the value of silver.

From 1850 to 1853, there was much hoarding of U.S. silver coins; most people refused to spend them. Many U.S. silver coins were purchased by speculators or moneychangers for amounts above their respective face values.

During the 1850s and 1860s, silver was worth more in United States dollars than it was supposed to be according to U.S. law, though silver reached a period high in 1859 before large quantities of silver ore were discovered in the West. By 1860, both pre-1853 and post-1853 silver coins were hoarded, mostly for political reasons and uncertainty about the future, rather than because of changes in the value of silver as a metal (bullion).

The U.S. Civil War began in 1861, and people throughout history tended to hoard silver and gold during times of war. Most Americans then owned at least a few Troy ounces of silver, often in the form of coins.

There are 480 grains in one Troy ounce, which remains the standard unit of measure for silver and gold. One Troy ounce is about 31.035 grams. In 1853, the specified weights and thus the respective silver content of half dimes, dimes, quarters and half dollars were reduced so people would spend them, rather than hoard them or sell them to speculators. The percentage of silver in each remained the same, 90%. For example, the Coinage Act of 1853 reduced the specified gross or total weight of a half dollar from 206.25 grains to 192 grains. For a long time, the weights of U.S. coins were officially measured in grains. Converted to grams, the reduction in 1853 of the weight of a half dollar was from 13.365 to about 12.44 grams.

As silver dollars were exempt from the Coinage Act of 1853, the silver content of silver dollars was not reduced. One silver dollar contained more silver than two new half dollars, four new quarters or ten new dimes. “The 1853 law retained the silver dollar without a reduction in silver content to make it appear that the United States were still bimetallic,” notes leading historian R. W. Julian, in response to my inquiries.

As silver dollars contained more silver per dollar of face value than all silver coins minted under the Coinage Act of 1853, silver dollars were rarely spent from 1853 to 1873. Silver dollars were then hoarded or traded for a premium over their respective face value. During the late 1850s, the U.S. Mint would not release silver dollars for face value; to obtain a silver dollar from the U.S. Mint or the U.S. Treasury Department in general, a premium had to be paid. In other words, it then costs more than a dollar to obtain a silver dollar.

The Coinage Act of 1873

The Coinage Act of 1873 slightly changed the weights of dimes, quarters, and halves. R. W. Julian’s research indicates that all the old planchets (prepared blanks) for these were melted by April 1873. In my opinion, an important point is that, if these old planchets (prepared blanks) had not been melted, most of them would have fallen within the allowed ranges of tolerance and thus could have been legally used to make new dimes, quarters, or half dollars after 1873.

The fact that the old planchets could have been legally used, if they had not been melted, suggests that the slight increase in specified weights in 1873 for dimes, quarters and halves was not important in the context of the value of silver. The changes in specified weights in 1873, which were slight, related to using the metric system and proposals for international standards for coinage.

The Coinage Act of 1873 terminated production of “standard” or normal silver dollars. Trade dollars were introduced, yet these contained more silver than silver dollars, 378 grains (about 24.5 grams). Normal or “standard” silver dollars were, from 1794 to 1935, specified to contain 371.25 grains of silver.

A Trade dollar was thus something much different from a U.S. silver dollar and was noticeably heavier. Trade dollars were not intended to be used as money in the United States, though a few did circulate domestically. Trade dollars were designed to facilitate trade between the U.S. and Asian nations, especially China, where silver was typically required as payment for goods. The face or nominal value of the Trade dollar was largely ignored by businessmen who focused on the silver content.

In 1873, the value of the silver content in a normal or “standard” silver dollar was around one dollar, thus by chance consistent with the Coinage Act of 1834 and the 16:1 — silver to gold ratio. From 1873 to 1876, however, the value of silver fell considerably, and each silver dollar contained notably less than one dollar worth of silver. Indeed, during 1876, the value of the silver in an uncirculated silver dollar that was minted from 1794 to 1873 averaged about $0.894, less than ninety cents!

People involved in various sectors of the silver industry were worried that the value of one ounce of silver would keep declining and that there would be less interest in silver coins. Before 1820, the British government had demonetized silver and Germany did so in the early 1870s.

Demonetization relates to a government eliminating or reducing the legal tender status of silver coins. If gold coins or pertinent gold-backed instruments are accepted at face value for all payments in a society, and silver coins are not accepted for all payments at face value in the same society, then that society is on a gold standard, assuming that the primary unit of currency is linked to gold. In the United States, the dollar is the standard unit.

Did the United States essentially demonetize silver via the Coinage Act of 1873? This law made clear that the “silver coins of the United States shall be legal tender at their nominal value for any amount not exceeding five dollars in any one payment” (Sect. 3586). Therefore, the recipient of a payment, whether a merchant, a creditor, or a tax collector, was NOT legally required to accept a payment in silver coins greater than five dollars in total. Payments in U.S. silver coins could be legally refused, even tax or court-ordered payments. Creditors could legally require payments in U.S. gold coins or gold certificates!

This provision in the 1873 law was in marked contrast to a relevant statement in the Coinage Act of 1837: silver “dollars, half dollars, quarter dollars, dimes and half dimes, shall be legal tenders of payment, according to their nominal value, for any sums whatever” (Section 9).

In terms of reducing the role of silver in the monetary system, did the Coinage Act of 1853 pave the way for the Coinage Act of 1873? The 1853 law said that silver coins minted in accordance with the reduced silver standard of 1853, from which silver dollars were exempt, “shall be legal tenders in payment of debts for all sums not exceeding five dollars.” While the Coinage Act of 1873 (Section 15) maintained the $5 limit, it went farther and applied the limit to all U.S. silver coins, not just half dimes, dimes, quarters, and half dollars minted since February 1853.

Effectively, the Coinage Act of 1873 erased the overall legal tender status of all U.S. silver coins in general. Many holders of silver coins felt robbed.

The Value of the Silver Standard & Bimetallism

In 1853 and in 1873, five dollars was not a large sum. Economists concluded that ‘silver was demonetized’ by the United States.

“With the exception of the paper-money period of 1862-187[4], the United States has expressed prices and contracts both actually and legally in the gold standard since 1834. For the purpose of bringing the law into harmony with the actual facts, gold was made the sole legal unit in 1873,” maintains J. Laurence Laughlin in The History of Bimetallism in the United States (New York: Appleton, fourth edition, 1898, Chapter XV). Vocal advocates for silver disagreed with Laughlin and other leading economists.

Owners of silver mines and people who put their savings in silver were scared that the world was moving in the direction of strongly favoring gold over silver in monetary frameworks. They argued that bimetallism was still the central monetary policy of the United States. After 1853, silver dollars were the only U.S. silver coins minted in accordance with the 16 to 1 — silver to gold ratio, which was established in the Coinage Act of 1834.

Except for Three Cent Silvers, from 1794 to some point in 1853, the net weight in silver of U.S. silver coins was legally mandated to be 3.7125 grains of silver (about 0.24 gram) for every one cent of face value, 1/100 of a dollar. A silver dollar was specified to contain 371.25 grains of silver (0.7734375 Troy ounce). A dime thus contained 37.125 grains of silver (about 0.077 Troy ounce) and a quarter contained 92.8125 grains (about 0.193 Troy ounce) of silver.

Silver dollars, including Morgan dollars, were the only post-1853 U.S. silver coins that contained 3.7125 grains of silver per one cent of face value. This was the standard for all U.S. silver coins before Three Cent Silvers were introduced in 1851. Three Cent Silvers were the first U.S. silver coins to be planned so that the bullion value of their silver content was substantially less than their face or nominal value. They were subsidiary or ‘fiat’ coinage.

Bimetallism requires a gold standard and a silver standard to co-exist in a framework with a government-fixed silver to gold ratio. With the termination of Liberty Seated silver dollars in 1873 and the five-dollar limit on the legal tender of U.S. silver coins, the longstanding policy of bimetallism was no longer in force. Advocates for silver, however, argued that the U.S. Congress did not have the right to quietly end the role of silver and place the nation on a gold standard in an unannounced manner. The Coinage Act of 1792 and some later laws emphasized that both gold and silver were the underpinnings of the U.S. monetary system. Indeed, advocates for silver emphasized that the Coinage Act of 1853 and especially the Act of 1873 clashed with earlier Coinage Acts, which were U.S. laws.

Shareholders and employees of silver mines were not the only people clamoring for silver. A substantial percentage of U.S. citizens had a notable quantity of silver coins in their possession. Even if such personal silver holdings were not vast in the grand scheme of the whole U.S. economy, silver holdings were important to individuals and families.

“Silver coins did not circulate east of the Rocky Mountains from 1862 to 1873. The silver dollar was a political football beginning in the late 1860s with the fall of silver values,” states R.W. Julian in answer to a question of mine.

As the market value of silver trended downward after 1873, supporters of silver in the U.S. Congress, especially Senator John Sherman and Representative “Silver Dick” Bland (pictured), pushed legislation. They demanded the return of the standard silver dollar, which must contain 371.25 grains of silver. Although infrequently used in commerce during the whole history of the United States, the U.S. silver dollar was very symbolic during the late nineteenth century. In the minds of the public, the U.S. silver dollar was connected to Western mining firms, farmers in the Midwest, rural Southerners, and poor people in general. Not only did so called ‘silver interests’ want a new silver dollar, they wanted the government to buy silver and coin silver dollars containing 371.25 grains of silver in each, so that the government would be attaching a face value of one dollar to a new coin that contained much less than one dollar worth of silver.

While U.S. gold coins were then legally worth their weight in gold, silver advocates wanted a silver dollar that was legal tender in any quantity yet may contain much less than $1 worth of silver. Moreover, they wanted the government to use general tax revenue to buy large quantities of silver to produce silver dollars. On Feb. 28, 1878, a new law was passed as a veto by President Hayes was overridden.

Show off Your Collection in the CAC Registry!

Have CAC coins of your own? If so, check out the CAC Registry–the free online platform to track your coin inventory, showcase your coins by building public sets, and compete with like-minded collectors!

The Bland-Allison Act

Two-thirds majorities in both the House and the Senate voted in favor of the Bland-Allison Act, which forced the U.S. Treasury to buy $2 million to $4 million worth of silver per month and to coin silver dollars in accordance with the pre-1853 standard for silver coins, 3.7125 grains of silver for each cent of face value. The main point of minting Morgan dollars in 1878 was for the government to stop or at least lessen the downward trend in the market value of silver with the idea that silver would play more of a role in the future. Many of those involved in the silver industry favored the Bland-Allison Act because they figured that the implementation of the new silver dollar program would cause the market value of silver as a metal to be significantly higher than it would otherwise have been.

Millions of Morgan dollars were minted and placed in government vaults. Leading economist J. Laurence Laughlin declares that the U.S. “Government was taking from taxes [on] its citizens about $30,000,000 a year, and with it buying the product of a special mining industry” (The History of Bimetallism, 1898, p. 241).

In his landmark book, Fractional Money, economist, and historian Neil Carothers concludes that Morgan silver dollars “were, in general, very badly received” (New York: John Wiley, 1930, page 232). People in rural areas of the South liked them. In the Midwest and the Eastern United States, Morgan dollars were shunned. In the more populated areas of the nation, neither businesses nor consumers wanted to regularly use Morgan silver dollars.

The Bland-Allison Act also enabled owners of silver dollars to deposit them with the U.S. Treasury in multiples of ten and receive silver certificates in return, a form of paper money. In 1878, silver certificates were issued in various denominations from $10 to $1000.

“Said certificates shall be receivable for customs, taxes, and all public dues, and, when so received, may be reissued,” according to the Bland-Allison Act (Section 3). Clearly, these certificates were intended to be true money, a widely accepted medium of exchange, which could be used to pay formal debts. As Laughlin explains, though, businesses used these silver certificates briefly for limited purposes. “From June 1878 “to the middle of 1880, almost all the silver coined stayed with the Treasury; only a few [silver] certificates were out” in circulation, states Laughlin (The History of Bimetallism, 1898, p. 242), Though only a small fraction of those minted ever circulated, Morgan dollar production began with tidal waves. In 1878, more than ten million were produced in Philadelphia alone, plus 2.2 million at the Carson City, Nevada, Mint and 9.75 million at the San Francisco Mint, for an annual total of nearly 22.5 million. Less than 1.5 million half dollars were struck in 1878.

I theorize that the main proponents of the Bland-Allison Act did not wish for Morgan dollars or linked silver certificates to circulate; silver advocates figured that there would be more upward pressure on the market value of silver if the U.S. government just bought silver, coined silver dollars, and then placed the silver dollars in U.S. Treasury vaults. Some Congressmen, however, figured that the Morgan silver dollar program should be more useful.

Morgan Dollars Entering the 1890s

Over the following dozen years, silver advocates became even more worried. All the government purchases of silver notwithstanding, the market value of silver trended downward during the 1880s. On average, during 1886, each silver dollar contained less than seventy-seven cents worth of silver ($0.77).

In 1886, Congress passed a law requiring the issue of $1, $2, and $5 silver certificates. The smaller denominations of 1886 complemented the larger denominations of silver certificates that were authorized in 1878, which were used mostly by businesses. The smaller denomination silver certificates of 1886 were designed as money for members of the general public, including poor people. Essentially, these silver certificates were ‘backed’ by Morgan dollars in U.S. Treasury Department vaults. The issuance of such silver certificates was a compromise among the politicians involved in debating monetary policies.

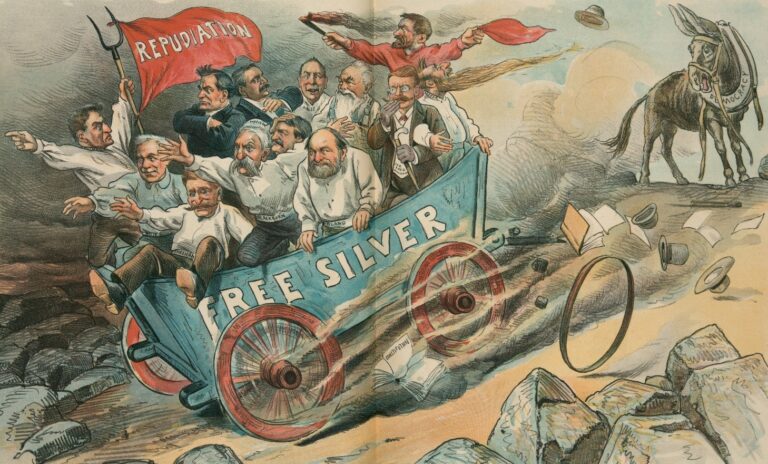

The demands of silver advocates were not satisfied by the minting of more than 340 million Morgan dollars from 1878 to 1889. Although the silver used to mint Morgans was purchased with taxpayer supplied funds, the value of silver kept falling. On average, the value of the silver in a silver dollar was less than seventy-five cents during 1889!

Owners of mining firms were becoming pessimistic about the future of silver. Poor people felt cheated by the role of gold at the center of the U.S. monetary system. Many farmers figured that business activities conducted with gold as a medium of exchange were harmful to their interests. Advocates of bimetallism were panicking because few substantial transactions in the economy were conducted with silver coins or silver certificates. The production of more than three hundred million Morgan dollars had not furthered their cause in the ways that silver advocates had hoped.

Gold bugs and free market-oriented voters in the Eastern United States were infuriated; they were paying taxes so that the government could mint and hold hundreds of millions of Morgan dollars. The fate of Morgan dollars stemmed from the outcome of a political conflict regarding U.S. monetary policy, which became intense in the early 1890s. The U.S. economy was a casualty, and the nation was never again the same. The second phase of Morgan dollars, beginning in 1890, was fantastic, and will be discussed next.

Images are copyrighted by DLRC (www.davidlawrence.com), except for the image of Richard P. “Silver Dick” Bland, which is in the public domain.

Copyright © 2023 Greg Reynolds

About the Author

Greg is a professional numismatist and researcher, having written more than 775 articles published in ten different publications relating to coins, patterns, and medals. He has won awards for analyses, interpretation of rarity, historical research, and critiques. In 2002 and again in 2023, Reynolds was the sole winner of the Numismatic Literary Guild (NLG) award for “Best All-Around Portfolio”.

Greg has carefully examined thousands of truly rare and conditionally rare classic U.S. coins, including a majority of the most famous rarities. He is also an expert in British coins. He is available for private consultations.

Email: Insightful10@gmail.com