by Greg Reynolds

This is an installment in my series on assembling a set ‘by date’ of Liberty Seated half dollars in Very Fine to Almost Uncirculated grades (VF-20 to AU-55). Here, Liberty Seated halves minted from 1861 to 1866 are covered, the Civil War era and the end of the ‘No Motto’ type. In 1866, the motto, ‘In God We Trust,’ was added to quarters, half dollars, silver dollars, half eagles, eagles, and double eagles.

In 1860, there was a sufficient supply of U.S. gold coins and silver coins in circulation for the needs of commerce. In contrast, during the early 1830s, U.S. gold coins were hoarded, melted, or exported on a large scale. Very few U.S. gold coins were then in circulation. In the early 1850s, this happened with silver coins, which were hoarded, melted, and traded.

Silver Ratio in U.S. Coins

The official government ratio of silver to gold was changed in 1834 from 15:1 to 16:1. In other words, in 1792, one ounce of gold was legislated to be worth fifteen ounces of silver and increased to sixteen ounces of silver in 1834. As the amount of silver in U.S. silver coins was unchanged in 1834, the amount of gold in each new gold coin was reduced so that gold coins would be more likely to be spent than to be exported or hoarded.

Until the 1870s, the market ratio, determined by traders not by the government, tended to vary in the 15:1 to 16:1 range. The “sharp and distinct fall, especially after 1874, and continuing … to 1885, has no parallel in the whole history of the precious metals. Within ten years the ratio of silver to gold … changed from an annual average relation of about 15½: 1 to nearly 19:1,” emphasizes J. Lawrence Laughlin in a landmark book, The History of Bimetallism (NY: Appleton, 1895, p. 162).

In 1852, there were too few silver coins in circulation. The market ratio was lower than the official government ratio of 16:1, an ounce of silver was really worth more than one-sixteenth of an ounce of gold. If a private citizen could sell one hundred dollars in U.S. silver coins for more than one hundred dollars’ worth of U.S. gold coins, then he would have a motive to sell or barter his silver coins rather than to spend them. Similarly, for a business that had a large quantity of U.S. silver coins, there was a profit to be made by selling, trading, or melting them rather than spending them, as the silver in the silver coins was worth more in gold than the official government ratio of 16:1.

The Coinage Act of 1853 reduced the silver content of half dimes, dimes, quarters, and half dollars, but not of silver dollars The adding of arrows to U.S. silver coins in 1853 notified consumers that the silver content of these coins had been reduced and encouraged people to spend new silver coins, rather than save them. While the reasons why arrows were added to silver coins are clear, it is not clear why they were removed. U.S. silver coins minted in 1856 did not have arrows.

U.S. Silver Coins in Circulation

In his widely acclaimed book, Fractional Money (NY: Wiley, 1930), Neil Carothers claims that, by 1854 or 1855, there were far too many U.S. silver coins in circulation. I have not found this claim in other leading references relating to the history of U.S. coinage. Indeed, I could not find substantiation of or even agreement with Carother’s claim in major academic texts of the time period or of the early 20th century.

R. W. ‘Bob’ Julian, the leading historian regarding U.S. coinage in the 19th century, explains that Carothers was partially correct. “The Philadelphia Mint under Snowden, but not the San Francisco or New Orleans Mints, bought silver bullion with silver coins” denominated below one dollar, “leading to an abundance. The law required that half dollars, quarters, dimes, and half dimes be paid out only for gold, but this provision was ignored by Mint Director Snowden,” Julian declares. “In 1858, due to numerous complaints about too many silver minor coins in circulation, the U.S. Treasury ordered Snowden to adhere to the law and mintages went down.”

In Philadelphia especially, there were too many U.S. silver coins in circulation. In 1855, many stores in Philadelphia accepted silver coins for only small payments. As the silver coins with arrows, those struck after the Coinage Act of 1853 was implemented, were legal tender for amounts up to just $5, creditors were not legally obligated to accept silver coins for payments greater than $5. Even in the 1850s, $5 was not a large sum. No branch of the U.S. government was legally obligated to redeem in gold coins the half dimes, dimes, quarters, and half dollars that were minted in accordance with the provisions of the Coinage Act of 1853.

As arrows were omitted from 1856 dies, half dollars dating from 1856 to 1865 became of the same design type as ‘With Drapery’ half dollars dating from 1839 to 1852, yet the 1856 to 1865 half dollars weighed less for important historical reasons. If the arrows had remained until 1865 and on the 1866-S ‘No Motto’ half dollars, then it would have been clear that the later ‘No Motto’ halves are different from the pre-1853 ‘No Motto’ halves. Would it have made sense to keep the arrows as part of the respective designs to indicate that the post-1853 Liberty Seated coins were struck in accordance with a different weight standard than the pre-1853 coins of the same respective design type?

Carothers (1930, p. 133) reports that “stores refused silver except in small payments, and banks even declined to accept deposits in silver coins” during late 1854 and 1855. Julian’s insights suggest that Carothers was probably referring to Philadelphia and other cities in the Middle Atlantic States. The Philadelphia Mint was producing more U.S. silver coins than were demanded by consumers and businesses.

It follows logically that Mint Director Snowden would no longer wish to encourage the spending of silver coins minted under the Coinage Act of 1853. Furthermore, it is likely that Snowden wished to discourage deposits of silver that would lead to the minting of more such coins, as there were too many in circulation in Philadelphia. Therefore, the local surplus of silver coins circa 1855 may have been the reason for Snowden to remove arrows from the designs of U.S. silver coins. As far as I know, I am the only person to have ever put forth this explanation for the removal of arrows.

J. Lawrence Laughlin focused on the success of the Coinage Act of 1853, particularly the effective circulation of silver coins with arrows. “The subsidiary [deliberately underweight → debased] coinage of silver introduced by the Act of 1853 served its purpose admirably,” concludes Laughlin, The History of Bimetallism (NY: Appleton, 1895, p. 86). The “business interests of the country were fully content” with circulating gold and silver coins, “and no trouble need have arisen,” Laughlin continues, “from any disturbances in our system of metallic currency had we been saved from the evils of our Civil War.”

Coin Shortages in the 1860s

By 1860, the supply of silver and gold coins in the U.S. was sufficient for commerce, and there was not a significant oversupply of silver coins. Historian Horace White notes, before “the Civil War the fiscal operations of the government were transacted exclusively with coin, by its own officers, without the intervention of banks” (Money & Banking, 4th ed., Boston: Ginn & Company, 1911, p. 107). While White’s statement is not exactly true, the overall point is important: To a large extent, there was a stable and efficient monetary order in 1860 in the United States, which involved the widespread daily use of gold and silver coins. By the middle of 1862, however, the monetary order had been ruptured and coin shortages were very serious.

For many years beginning in 1862, most silver coins were hoarded, kept as reserves, retained as savings, exported, or melted. Commerce was transacted with copper coins, copper tokens, postage stamps, privately issued paper money and coupons, banknotes that were officially sanctioned in the past, negotiable paper issued by local governments, and paper money issued by the United States (federal) government.

In response to an inquiry of mine, R. W. Julian remarks that privately issued “Civil War tokens helped somewhat as did U.S. Three Cent Silvers, which were not hoarded until late 1862 or early 1863. From 1862 to the spring of 1864 copper-nickel Flying Eagle and Indian cents were also hoarded.” The U.S. monetary system was in disarray.

During late 1861 and early 1862, a large number of banks ceased disbursing gold coins, silver coins, and all bullion in ordinary business. To most merchants and consumers, silver coins, gold coins and other forms of precious metals were not available for commerce.

“The absence of small silver [coins or bars] had brought into existence tokens, tickets, checks, and substitutes of every description, issued by merchants and shopkeepers,” Laughlin explains (1895, p. 89). In addition to various kinds of privately issued tokens and paper instruments, people began to use U.S. postage stamps as currency. This led to problems, misunderstandings, and confusion. Postage stamps were not a viable alternative to coins.

The federal act of February 25, 1862, authorized the issue of $150 million worth of paper money by the U.S. Treasury Department, a radical and frightening measure at the time. During the 19th century, previous issues of ‘notes’ or other financial instruments by the U.S. government served specific purposes and were not intended for wide circulation among the general public as money.

After issuing federal paper money, “Greenbacks,” of the kinds of denominations that people expect of paper money, the federal government, later in 1862, issued paper money in denominations below one dollar, ‘fractional currency.’ Actually, the first type of fractional currency was patterned after postage stamps and is often called “postage currency.” Later issues of fractional currency by the U.S. government were designed more like paper money tended to be designed, except that they were significantly smaller in size than one-dollar bills, truly fractional. Historian Bob Julian emphasizes that most consumer transactions “east of the Rocky Mountains from 1862 to 1873 involved fractional paper currency.”

The Minting of Silver Coins in the 1860s

During the 1860s, the West was very sparsely populated. The vast majority of U.S. citizens lived in the East or the Midwest. Although U.S. silver and gold coins were not then circulating widely, they were minted.

Curiously, the coin rarities that came about during the era of the U.S. Civil War (1861-65) tended to be of other denominations. Half dollars are the least scarce of all silver coins minted during the U.S. Civil War. Especially for coins dating from 1863 to 1865, the mintages of half dollars were dramatically larger than the corresponding mintages of Three Cent Silvers, half dimes, dimes and quarters.

As silver dollars were exempt from the weight reductions required by the Coinage Act of 1853, silver dollars were overweight in comparison to silver coins of other denominations and also in absolute terms. During the 1850s and 1860s, each uncirculated silver dollar of any date contained notably more than one dollar figured in gold.

Consequently, few silver dollars were minted from 1853 to 1865. They are not great rarities in the present because parts of their very low mintages were not intended for commerce during this time period. During the 1850s, many silver dollars were made for influential officials, collectors and others who are unknown to current historians.

“Prior to 1860, during the tenure of Snowden as U.S. Mint Director, silver dollars were sold in Proof or uncirculated for $1.08 each,” R. W. Julian reveals in correspondence with me.

Silver dollars were not struck in San Francisco during the 1860s and half dollars were struck there. Mintages during the years 1862 and 1864 provide evidence that silver dollars were not then playing much of a role in the economy. Despite the fact that they were rarely spent, 1862 to 1865 half dollars were serving important commercial purposes.

In 1862, 11,540 silver dollars were minted in Philadelphia and zero were minted in San Francisco. In contrast 253,000 half dollars were minted in Philly and 1.35 million were minted in San Francisco. More than 900,000 quarters were minted in Philly, though just 67,000 quarters were minted in San Francisco. The mintage of dimes in 1862 was similar to that of quarters, 847,000 in Philly and 180,750 in San Francisco.

In 1864, just 30,700 U.S. silver dollars were minted, again all in Philadelphia, yet 379,100 half dollars were minted in Philly and 658,000 in San Francisco. In other words, more than one million half dollars were minted in 1864 and just 30,700 silver dollars.

In 1864, only 11,000 dimes were minted in Philly and 230,000 in San Francisco. As for quarters, the mintage in Philadelphia was 93,600, less than one-fourth of the mintage of half dollars in Philadelphia in 1864. The difference between the mintage of 1864-S half dollars and quarters in San Francisco is dramatic, 658,000 versus 20,000; quarters amounted to about 3% of the half dollar total.

As effectively the largest silver denomination during the 1850s and 1860s, half dollars were used for bank reserves, personal and business savings, hoarding, collateral, fulfillment of contracts that required silver, etc. They were demanded for purposes other than to be spent at face value. Civil War era half dollars were struck in substantial quantities, and often saved. They are not rare in the present and many collectors can practically seek to acquire them.

The 1861-O Liberty Seated Halves

Before mentioning some recent public sales of half dollars from the Civil War era, there is a need to reflect upon the curious case of the 1861-O. Although historians have concluded that apparently regular 1861-O halves were struck after the U.S. Treasury Department lost control of the New Orleans Mint, it is hard to tell which 1861-O half dollars were struck by the federal government and which were struck while the New Orleans Mint was held by rebel forces.

Louisiana seceded from the union on January 26, 1861, and was an independent nation for less than two weeks. On February 4, 1861, the State of Louisiana joined the Confederacy, the rebel organization that was revolting against the United States of America.

There are some 1861-O halves that are known to have been struck while the New Orleans Mint was under the auspices of the Confederate States of America (CSA). Patterns for Confederate half dollars were struck using a regular USA obverse die and a new CSA reverse die, which was designed and forged by the Confederates.

Specialists in half dollar varieties maintain that this same USA obverse die, which was used to make CSA pattern half dollars, remained in the press, and was paired with a regular USA reverse die to produce apparently regular United States half dollars for the benefit of the CSA. These so-called CSA obverse 1861-O halves sell for large premiums over all other 1861-O halves. Although these are historically fascinating, there is not a need for a collector of Liberty Seated halves by date to acquire one of these so-called CSA obverse 1861-O halves in order to complete a set by date.

As a majority of 1861-O halves were struck while the New Orleans Mint was controlled by the Confederacy anyway, does it make sense to pay an extremely large premium for those that were struck with a worn and fractured obverse die? Moreover, the apparently regular USA 1861-O half dollars minted while the New Orleans Mint was controlled by the CSA were struck with dies that were made in Philadelphia and shipped to New Orleans before the U.S. Civil War began. Although there is some truth to the notion that they are Confederate halves, most 1861-O halves were really illegal products that were struck from plundered dies on a plundered press. It is questionable as to whether they are coins at all, in my view

Besides, the collecting of confederate numismatic items is a separate and distinct specialty, which is a subject apart from collecting Liberty Seated halves by date. Indeed, there is no need to think about the CSA while collecting Liberty Seated halves by date.

Show off Your Collection in the CAC Registry!

Have CAC coins of your own? If so, check out the CAC Registry–the free online platform to track your coin inventory, showcase your coins by building public sets, and compete with like-minded collectors!

Recent Sales of Civil War Era Halves

Typical 1861-O and normal 1861 halves are scarce, though are not really hard to find. In January 2022, the firm of Gerry Fortin sold a CAC approved XF-45+ grade 1861 for $350, with PCGS serial #31609897. DLRC sold a CAC approved XF-45 grade 1861-O on Nov. 28, 2021, for $600 and a CAC approved AU-55 grade 1861-O half on Dec. 12, 2021, for $1200, twice as much.

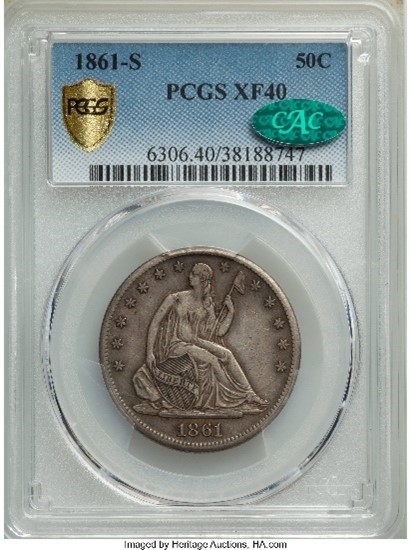

CAC has approved just thirty-four 1861-S halves, though a majority of those are in the XF to AU grade range. On March 31, 2020, Heritage sold a CAC approved XF-40 grade 1861-S for $456. In October 2022, this $456 result would be considered a low retail price.

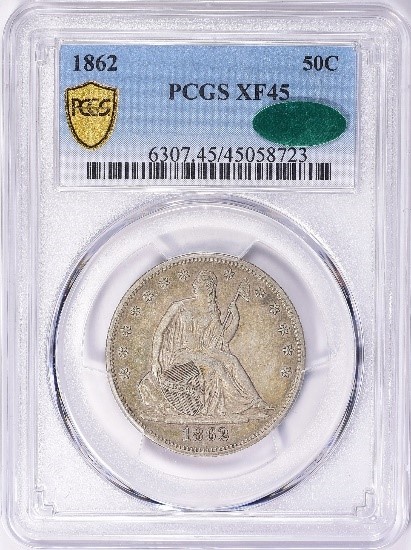

On Oct. 9, 2022, GreatCollections sold a CAC approved XF-45 grade 1862 half for $704.25. On Aug. 31, 2021, Stack’s Bowers auctioned a CAC approved XF-45 grade 1863 for $840.

The remaining halves of the ‘No Arrows, No Motto’ type are not especially expensive. Given their scarcity and historical importance, they are good values in a logical sense. It may be a challenge, however, to find and acquire relatively original examples for fair collector prices. Again, patience may be required.

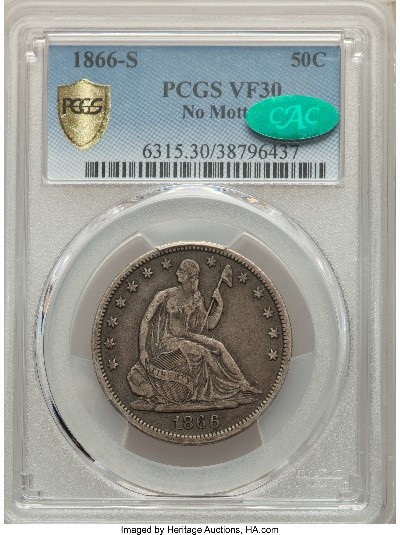

The ‘No Motto’ 1866-S is a curiosity. Actually, 1866-S ‘No Motto’ half eagles, eagles and double eagles, were minted, too. A law required all quarters, half dollars, silver dollars, half eagles, eagles and double eagles to feature the motto, ‘In God We Trust,’ on the reverse. All the dies were then prepared in Philadelphia. Late in 1865, 1866 obverse dies were shipped to the San Francisco Mint. The new reverse dies, with ‘In God We Trust,’ however, did not arrive for months, well into the year 1866. During part of the year, the San Francisco Mint paired new 1866 obverse dies with ‘No Motto’ reverse dies that they had received in the past.

The only silver 1866-S ‘No Motto’ coins are half dollars. It is probably fair to theorize that 265 survive. Among those 1866-S ‘No Motto’ halves that have received numerical grades from PCGS or NGC, CAC has approved thirty-seven.

In December 2021, Gerry Fortin sold a CAC approved VF-30 grade 1866-S ‘No Motto’ half for $1600. Other than a few varieties that really should not be regarded as distinct dates or collected as if they were, the 1866-S is the most expensive ‘No Drapery, No Motto, No Arrows’ half dollar.

On the whole, a complete set of circulated Liberty Seated ‘No Motto’ half dollars is not difficult to assemble and a complete set by date is not especially expensive in the context of U.S. silver coins from the middle of the 19th century. The ‘With Motto’ dates from the 1860s and 1870s constitutes a different topic, which will be addressed next.

Images are copyrighted by GreatCollections.com, the firm of Gerry Fortin (seateddimevarieties.com), and Heritage Auctions (ha.com).

Copyright © 2022 Greg Reynolds

About the Author

Greg is a professional numismatist and researcher, having written more than 775 articles published in ten different publications relating to coins, patterns, and medals. He has won awards for analyses, interpretation of rarity, historical research, and critiques. In 2002 and again in 2023, Reynolds was the sole winner of the Numismatic Literary Guild (NLG) award for “Best All-Around Portfolio”.

Greg has carefully examined thousands of truly rare and conditionally rare classic U.S. coins, including a majority of the most famous rarities. He is also an expert in British coins. He is available for private consultations.

Email: Insightful10@gmail.com