by Greg Reynolds

Please see part 1 for introductory remarks about Liberty Seated dimes, and discussion of the ‘No Drapery’ and ‘With Drapery’ types. In numerous articles, I have listed the thirteen design types of silver dimes. Here, the focus is on the second three of six design types of Liberty Seated dimes.

8. Liberty Seated – Arrows & Stars on Obverse (1853-55)

9. Liberty Seated – Legend on Obverse (1860-73, 1875-91)

10. Liberty Seated – Arrows & Legend on Obverse (1873-74)

Six Liberty Seated dimes are needed for a complete type set of all silver dimes, though such a mini-set of six coins can logically fit into other kinds of larger sets. Some collectors assemble type sets of all Liberty Seated denominations: half dimes, dimes, quarters, half dollars and silver dollars. Other collectors specialize in particular metals or time periods. It is common and sensible for collectors to assemble type sets of all U.S. coin types that were first minted during the period from 1866 to the 1930s.

Such an 1866 to 1930s type set could be limited to one or two metals or could include U.S. coins struck in all metals: copper (bronze), nickel, silver and gold. ‘With Motto’ quarters, half dollars, silver dollars, $5 gold coins, $10 gold coins and $20 gold coins were all first minted in 1866. Five cent nickels were introduced during this same year. Many collectors, though, assemble silver-only type sets that are straightforward, interesting and not expensive.

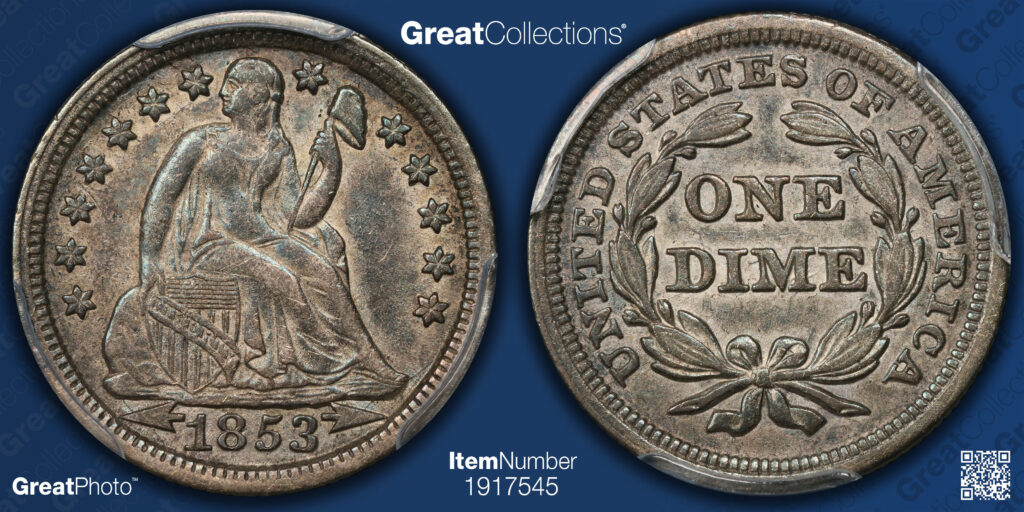

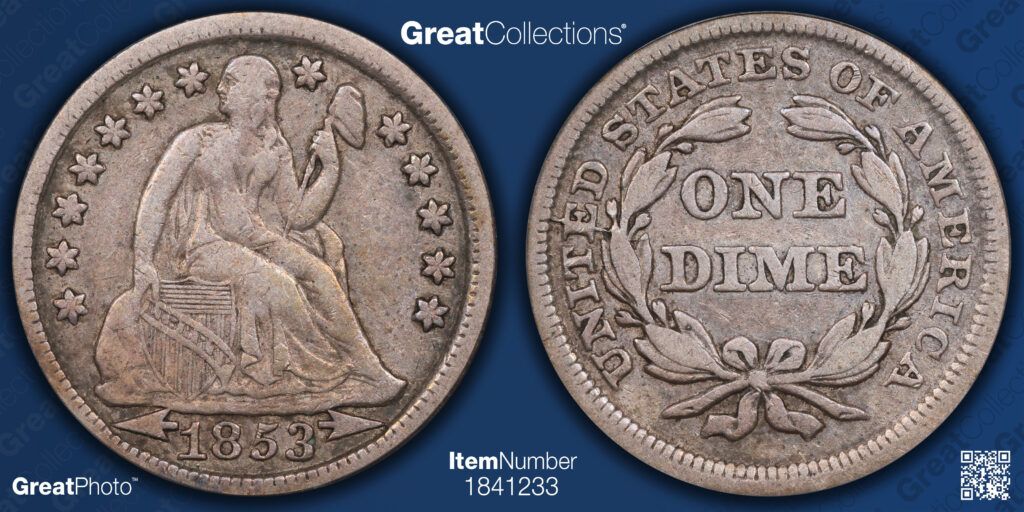

#8 Liberty Seated – Arrows & Stars on Obverse (1853-1855)

Arrows were added to the obverse design in 1853 to indicate that the silver content had been reduced. People had been hoarding or exporting U.S. silver coins because the value of silver in relation to gold had increased. The California Gold Rush led to a massive increase in the supply of gold, so silver became relatively scarcer. The presence of arrows advertised the reduction in silver content to encourage more people to spend dimes, rather than hoard them or sell dimes as silver bullion.

For the Philadelphia Mint issues ‘With Arrows,’ 1853, 1854 and 1855, the CPG-CAC retail price estimates for dimes in Very Fine grades are in the range of $45 to $60, though these estimates could be low. It is hard to tell as there are very few such coins in the CAC pop report and the details surrounding their sales are not publicly available. Relatively inexpensive coins are often sold at coin shows for cash.

The Coinage Act of 1853 did not take effect immediately. Dimes minted before June 1853 could legally be of the old design, without arrows, and of the old weight standard. There thus exist 1853 ‘No Arrows’ dimes of type #7 and 1853 ‘With Arrows’ dimes of type #8. As all genuine 1854, 1854-O and 1855 dimes must have arrows, there is not a need to mention the word ‘arrows’ in regard to each of these. Arrows were not removed from the design format until the coins of 1856 were minted.

On June 15, 2025, GreatCollections sold a CAC approved VF-20 grade 1853 ‘With Arrows’ dime for $90.20. On April 10, 2022, DLRC sold a CAC approved AU-50 grade 1853 ‘With Arrows’ dime for $251. On June 15, 2025, GreatCollections sold a CAC approved AU-55 grade 1854 dime for $653.40.

Back in 2019, Stack’s Bowers sold a CAC approved Fine-15 grade 1855 dime for $40. It might bring considerably more if Stack’s Bowers auctions this same coin in 2026. On March 27, 2023, Stack’s Bowers auctioned a CAC approved AU-55 grade 1855 for $504.

It is probably best not to include dimes minted from 1856 to 1859, or an 1860-S, in a type set, as these tend to be confusing. In terms of design elements, these are of the same type as those minted from the middle of 1840 until early 1853, but they adhere to the weight standard that came into effect on June 2, 1853. They are not logical choices to represent a type that began before 1853, and are not considered to constitute a design type of their own with a pre-1853 design and a post-1853 weight. Indeed, dimes dated from 1856 to 1859, and the 1860-S, were minted in accordance with the weight standard required by the Coinage Act of 1853, yet they do not have arrows.

The Removal of Arrows in 1856: A Theory

A question remains as to why the arrows were removed from the design by 1856 even though the reduction in silver content, which was indicated by those arrows, became permanent. In an article in the Greysheet in 2023, I put forth a theory.

According to noted researchers in the past, especially Neil Carothers and Don Taxay, there was a large surplus in the economy of reduced weight (type #8) ‘With Arrows’ dimes by 1855. Many store owners and banks on the East Coast of the United States made clear that they no longer wanted 1853 to 1855 ‘With Arrows’ dimes. These type #8 dimes then became much less liquid than dimes of the original, pre-1853 standard for silver content, which was clearly established in the Coinage Act of 1792.

The arrows of 1853, I argue, were originally intended to announce the reduction in silver content and thus to encourage people to spend dimes. Indeed, the arrows put a spotlight on the reduction in silver content. In 1853, there was a compelling reason to advertise the reduction in silver content to discourage hoarding or melting and to encourage spending of dimes.

After hoarding faded, and many hoarded dimes were spent, there were too many dimes around, especially 1853 to 1855 ‘With Arrows’ dimes with reduced silver content. I theorize that some in the U.S. Treasury Department no longer wished to use arrows to advertise the reduction because they wanted merchants and banks to accept silver coins minted after June 2, 1853. Without arrows to remind them, many people would forget or never learn that post-1855 dimes each contained less silver than pre-1853 dimes.

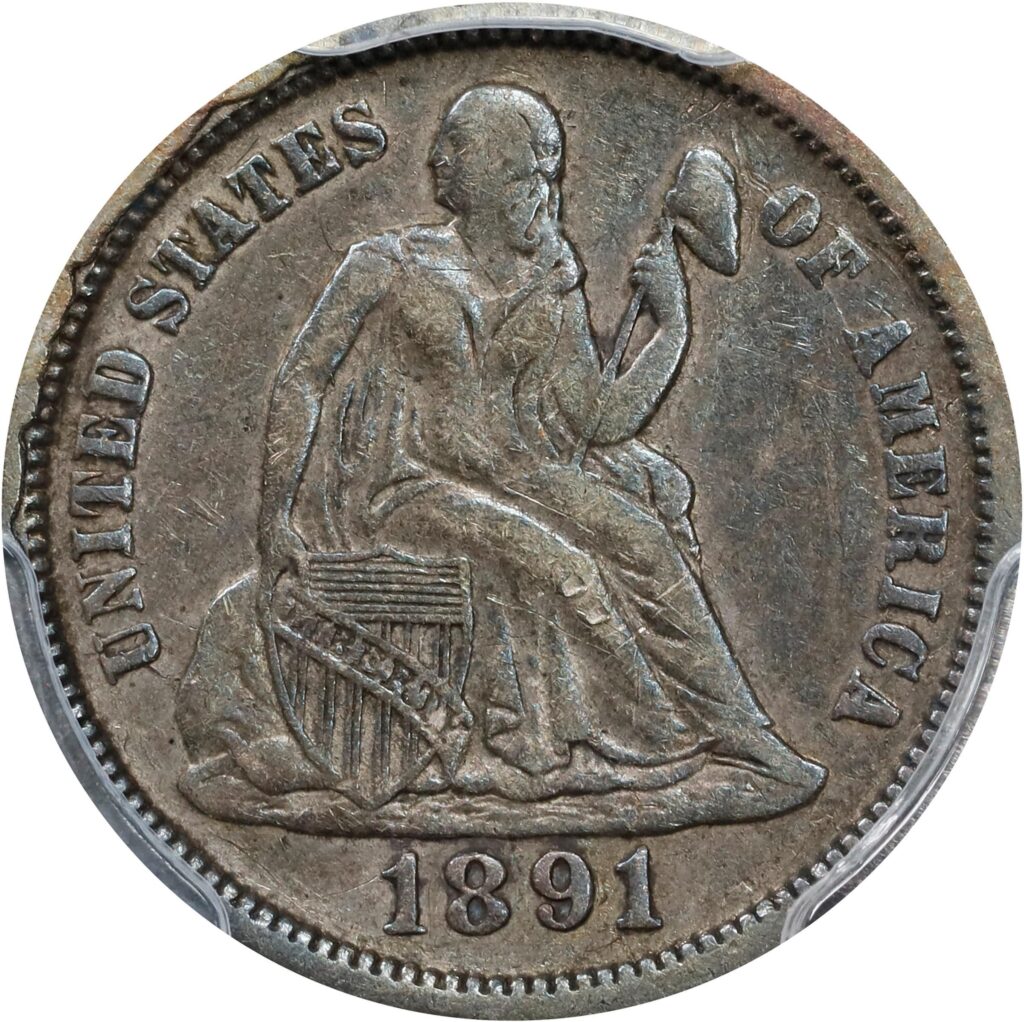

Type #9 Liberty Seated – Legend on Obverse (1860-1873, 1875-1891)

In 1860, the name of our nation was moved from the reverse (tail) to the obverse (head side) and stars were removed from the design of dimes. Liberty Seated dimes of type #9 were engraved by James Longacre. He did not, however, merely edit the design of type #7 (1840-60, except 1854-55). In my opinion, Longacre should be credited as a designer as well.

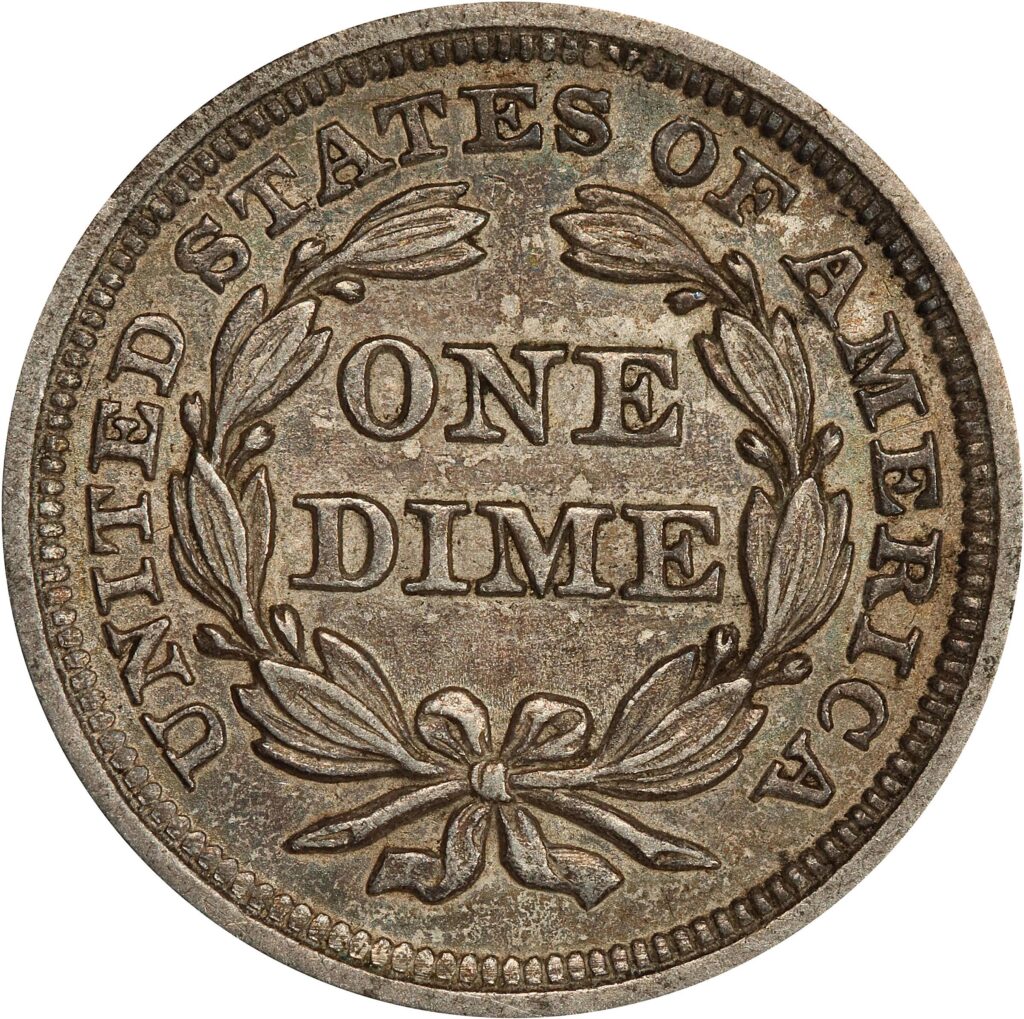

The wreath became much more elaborate. Longacre modified it to reflect trees and agricultural products associated with the United States.

Longacre changed the Liberty Seated concept. Indeed, I find Longacre’s Liberty Seated design for dimes to be markedly different from both the 1840-60 ‘With Drapery’ design (type #7) and Christian’s Gobrecht’s conception (type #5).

The best way for collectors to see the differences is to inspect well detailed type #9 and type #7 dimes with a magnifying glass while they are side-by-side. In my view, the designs of the female personifications of Miss Liberty on types #5-6, #7-8, and #9-10 are of three notably different styles and are unmistakably the works of different artisans. Admittedly, though, some differences are subtle.

Circulated Type #9 Dimes

The 1860, 1861, 1872, 1877, and 1878, plus most of the Philadelphia Mint dates from the 1880 to 1891 are inexpensive. Many dimes of these dates, however, have never been certified or have yet to be sent to a CAC office. In addition, there are a sizable number that failed to qualify for numerical grades in the opinions of experts at CAC because they have been harmfully cleaned, badly scratched, beat up, doctored, or for other reasons.

Circulated, CAC approved, type #9 Liberty Seated dimes publicly appear at times, though not very often. Most collectors probably buy them directly from dealers or at small coin shows.

Price guides tend to underestimate the values of CAC-stickered or CACG graded, circulated Liberty Seated dimes of the least scarce dates. On June 29, 2025, GreatCollections sold a CAC approved VF-35 1875 dime for $117.70. The CPG-CAC medium retail estimate was $34.

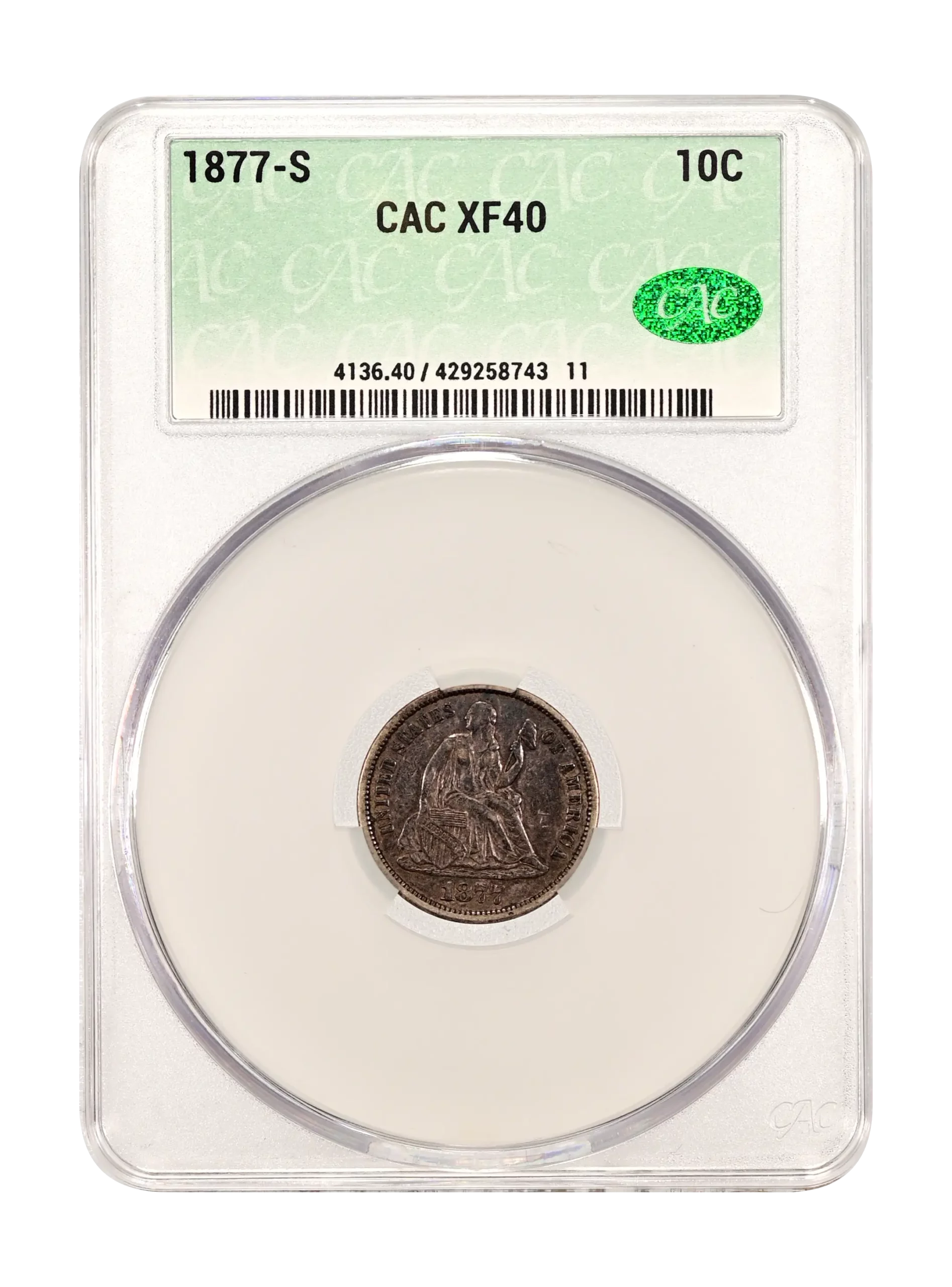

On July 13, GreatCollections sold a CACG graded XF-40 1877-S dime for $112.19. The CPG-CAC retail estimate was $75.

On June 15, GreatCollections sold a CAC approved XF-45 grade 1887 for $102.19. The CPG-CAC medium retail estimate was $65.

On Sept. 7, 2025, GreatCollections sold a CAC approved XF-45 grade 1890 dime for $178.77. The CPG-CAC retail estimate today, Sept. 11, 2025, for that coin is $65, a little more than one-third of this price realized. On March 20, 2025, Stack’s Bowers auctioned a CACG graded AU-58 1890 dime for $168, a result which is consistent with the CPG-CAC retail estimate of $170.

On June 15, GreatCollections sold a CAC approved VF-35 grade 1891-O for $89.10, nearly twice as much as the CPG-CAC retail estimate of $49. On May 21, 2025, Stack’s Bowers sold a CAC approved XF-40 grade 1891-O dime for $105, way above the CPG-CAC retail estimate of $60.

Generally, collectors should not rely upon price guides. It is important for a collector to think about the values of particular coins to him or her.

Type #10 Arrows & Legend on Obverse (1873-1874)

The adding of arrows to the design of dimes in 1873 is almost entirely unrelated to the adding of arrows to dimes in 1853. The Coinage Act of 1873 slightly increased the weights of dimes, quarters and half dollars. It was important in 1853 to inform consumers of the 7% decrease in silver content of dimes so that people would spend them, rather than hoard or melt them. There was not a rational reason to repeatedly remind people of a very slight increase in silver content of dimes in 1873, as this could encourage hoarding or be irritating.

Earlier laws are relevant. The Coinage Act of 1837 did not change the amount of silver in each dime, which remained 37.125 grains, but it changed the total weight of a dime from 41.6 grains (2.696 grams) to 41.25 grains (2.672 grams). The Coinage Act of 1853 reduced both the silver content and the total weight of a dime, which went from 41.25 grains to 38.4 grains (2.48 grams). The Coinage Act of 1873 increased both the silver content and total weight of a dime to a trivial extent, from 38.4 grains (=2.48 grams) in total to 2.5 grams (38.58 grains), within the previously established allowable deviation. Therefore, a precisely proper weight dime planchet (prepared blank) made under the Coinage Act of 1853 could have in theory been legally used to strike 1873 or 1874 dimes, with arrows.

R. W. Julian, the leading historian of the U.S. Mint, informed me that “the old dime planchets on hand were melted after March 31, 1873.” My point in this context is that the increase in weight was so small that a prepared blank (dime planchet) of proper prior weight, before the weight increase was effected, could have been legally used to make dimes under the new weight standard, which fell with the allowed standard deviation.

The Coinage Act of 1792 defined a U.S. dollar as 371.25 grains of silver (=24.0566 grams). This definition was still valid when the last Peace silver dollars were minted in 1935, and was not formally revised until the 1960s. The reduction of the silver content in a dime mandated by the Coinage Act of 1853 resulted in each post-May 1853 to pre-April 1873 dime being worth approximately $0.0930909 rather than legally being worth $0.10 in silver.

The Coinage Act of 1873 increased the silver content of a dime, such that a dime’s value in silver rose to $0.0933075, according to the legal definition of silver’s value in the U.S. The increase in the value in 1873 of silver in a dime was thus $0.0002166, about 1/47 of one cent. In other words, with this increase, forty-seven new dimes altogether had one cent worth of silver more than forty-seven old dimes. Each dime still had approximately 9.3 cents worth of silver, less than ten cents worth of silver anyway, according to the legal definition, not the market rate, which varied.

In regards to most people, this change in weight in 1873 did not make any difference. Logically, there would be no point in adding arrows to notify people of the increased silver content, as the increase was so tiny.

According to J. Laurence Laughlin, the leading economist in the U.S. during the late nineteenth century, the average value of silver during the year 1852 was the same as it was during the year 1871. The hoarding of dimes was a terrible problem in 1852. In 1872 and early 1873, government officials must have been concerned that the increase in silver content in dimes might cause people to hoard them again.

For millennia, during times of crisis or extreme uncertainty, people tended to hoard silver coins. There was a great deal of political conflict and concerns about the monetary system in the United States during the 1870s. During the early 1850s and again at times during the 1860s, the general public in the United States did hoard silver coins, and in the early 1870s as well. It follows logically that the officials of the U.S. Mint would not wish to use arrows to notify consumers of an increase in silver content. They had a motive to keep quiet about the increase as they wished for U.S. silver coins to be spent, not hoarded.

If the slight increase in the silver content was not the true reason for the arrows, then what was the reason? The use of metric measurements for the weights of dimes, quarters and half dollars could have been the reason for the placement of arrows on dimes of 1873 and 1874. Somehow, though, this does not seem to be a logical explanation, though it could be true.

To the best of my recollection, the Coinage Act of 1873 was the first law to specify weights of U.S. silver coins in the metric system, grams rather than grains or ounces. Some historians figured that there was a movement at the time to adopt the metric system for U.S. coinage and this was the reason for the arrows on dimes, quarters and half dollars in 1873 and 1874. While I understand why an historian would think that there was a jump in the direction of adopting the metric system, I theorize that this was not true at all.

Undoubtedly, at least a couple U.S. Mint officials wished for the U.S. to adopt the metric system, at least in regard to coinage, or thought that the metric system would eventually be used for coinage anyway. In the United States during the nineteenth century, however, there were just very small groups of people who favored the adoption of the metric system, especially scientists, lab technicians, and businessmen who had particular reasons to favor the metric system.

The adoption of metric weights for three U.S. silver denominations in 1873 relates to efforts in the second half of the nineteenth century by European nations to bring about better international consistency in coinage. There were conferences and agreements among some European nations that fixed a gold-silver price ratio, which was valid across national boundaries, and made coin denominations in Europe more consistent than they would otherwise have been. A handful of members of the U.S. Congress were supportive of international efforts to standardize coinage; they favored changes in U.S. coinage to achieve greater standardization for use of coins in trade and travel across national boundaries.

It is especially relevant that the Latin Monetary Union (LMU) was formed in 1865 by several European nations and more members joined later. France was the leader.

The metric weights in the Coinage Act of 1873 were a political connection to French coinage that bordered on fantasy. In the early 1870s, the French revised their coinage system. The new one franc silver coin, which was introduced in 1871, weighed 5.0 grams.

The French fifty centimes silver coin weighed 2.5 grams. I theorize that this is the reason why the weight of the U.S. dime was changed to 2.5 grams in 1873, to move closer to the French monetary system. In the nineteenth century, France was a superpower. Earlier, France played an important role in the American Revolution, on behalf of the American colonists.

Put differently, the change in weights in the Coinage Act of 1873 for dimes, quarters and half dollars was a political connection to French coinage and to the idea of an international coinage standard, but not a practical connection. U.S. silver coins and French silver coins did not become interchangeable in general.

Indeed, the idea of international coinage standards was complicated, especially since there were political and economic obstacles. Besides, there was not a law or accepted plan to adopt the metric system in the U.S. or to modify U.S. coinage to match international specifications.

The vast majority of U.S. citizens were not interested in the metric system. People were proud of the British-American system of weights and measures.

It would have made sense for the members of the general public to be notified or at least reminded about a new law that affected their money and their lives. By seeing arrows on newly minted coins, U.S. citizens learned that there was a new law, the Coinage Act of 1873. Not everyone subscribed to newspapers or spent much time reading.

It is not true that the metric weights for three denominations in the Coinage Act of 1873 related to any kind of a solid plan to adopt the metric system for coinage or in society overall. There was much, however, in the Coinage Act of 1873, really a game-changing law in the history of the United States. It follows that many people wished to learn about, or at least be notified of its existence. I theorize that the use of arrows on coins in 1873 and 1874 was a form of notification, which was ethical and made people curious. Those who were interested could learn more.

Circulated 1873-1874 ‘With Arrows’ Dimes

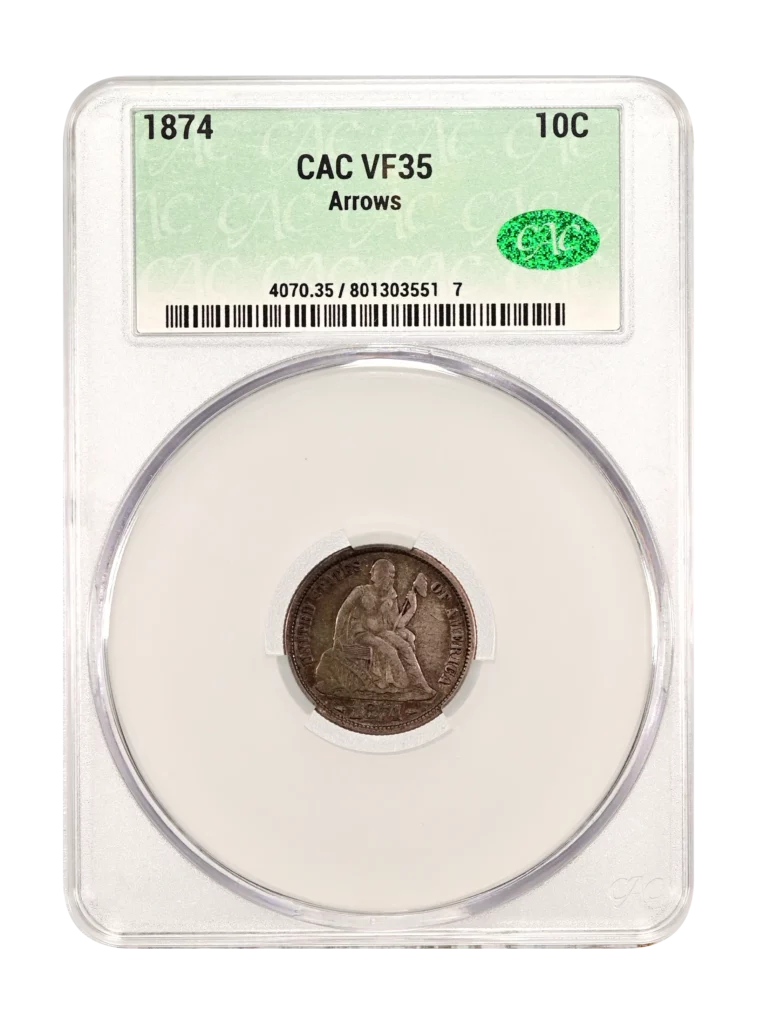

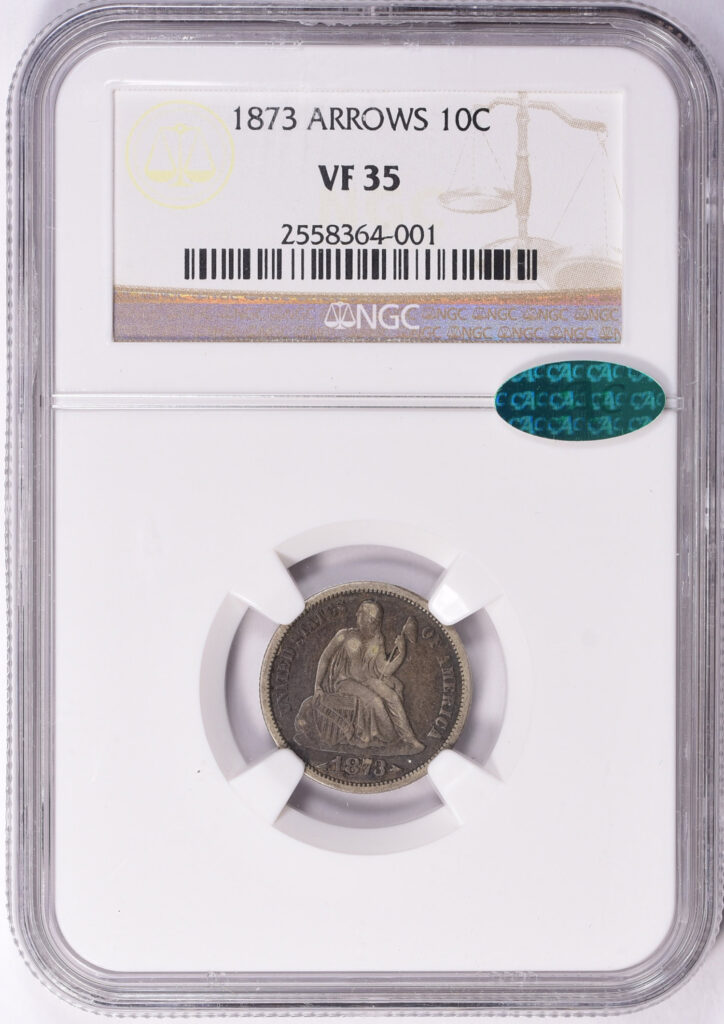

It is not difficult to acquire a circulated 1873 ‘With Arrows’ or 1874 dime. While some 1873 dimes do not feature arrows, probably because they were minted before the Coinage Act of 1873 was fully implemented, all genuine 1874 dimes were struck with arrows. The new law took effect on April 1, 1873.

On March 10, 2024, GreatCollections sold a CAC approved, NGC graded VF-35 1873 ‘With Arrows’ dime for $126.79. Almost one year earlier, on March 26, 2023, GreatCollections sold a CAC approved, PCGS graded XF-40 1873 ‘With Arrows’ dime for $182.60.

On March 10, 2025, precisely one year after the sale date of the just mentioned VF-35 grade 1873, Heritage sold a CAC approved XF-45 grade 1874 ‘With Arrows’ dime for $264. The CPG-CAC medium retail estimate for a VF-20 grade 1874 or 1873 ‘With Arrows’ is $95, though this is a certification rarity. It may be necessary to budget more than $125 for a Very Fine grade representative of the 1873-74 ‘With Arrows’ (#10) design type.

A CAC-only type set of Liberty Seated dimes is not hard to assemble and circulated coins cost much less than Choice to Gem Uncirculated coins of these types. Moreover, the different Liberty Seated designs reflect the works of different artisans and are tied to dynamic episodes in the monetary history of the United States. As type sets of Liberty Seated coins tend to be characterized by Philadelphia Mint products, such a set can easily be expanded by including coins from multiple mints: New Orleans, Carson City and San Francisco. Also, it is very easy to add a Mercury dime, a Barber dime, and a Capped Bust dime to a type set of Liberty Seated dimes.

Copyright © 2025 Greg Reynolds

About the Author

Greg is a professional numismatist and researcher, having written more than 775 articles published in ten different publications relating to coins, patterns, and medals. He has won awards for analyses, interpretation of rarity, historical research, and critiques. In 2002 and again in 2023, Reynolds was the sole winner of the Numismatic Literary Guild (NLG) award for “Best All-Around Portfolio”.

Greg has carefully examined thousands of truly rare and conditionally rare classic U.S. coins, including a majority of the most famous rarities. He is also an expert in British coins. He is available for private consultations.

Email: Insightful10@gmail.com